By: David Dennis

When we think of a roadway, most of us think of the asphalt or concrete that we are riding on.

Little thought is given to the ditches that line our roads or how water flows off our roadways. A Texas A&M Transportation Institute (TTI) researcher has come up with an automated way of determining if those ditches are doing their job properly and keeping water flowing where it should.

Most transportation agencies maintain an extensive data collection catalog documenting the performance of roadways in a state. Charles Gurganus, associate research engineer in TTI’s Pavements and Materials Division, is studying an automated method of providing highway agencies and roadway managers with right-of-way line to right-of-way line roadway surface geometric information.

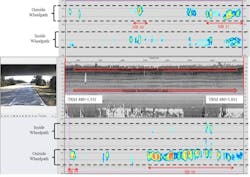

A data collection map charting rutting inside and outside the wheelpath on a roadway.

Guiding light

Utilizing LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology, Gurganus is able to collect extensive roadway geometric data, including roadway cross slopes, super elevations, front slope steepness and drainage areas on a roadway. The technology also can determine the depth of a roadside ditch and its offset related to the nearby pavement structure. All data can be collected at highway speeds.

“It’s almost like we are proving what has always been intuitive about roadway work. We think shallow ditches close to the edge of the pavement may cause pavement problems. We think deeper ditches farther away from the pavement edge with a good longitudinal grade are more desirable. Now we can measure that at a network level and compare it to pavement performance,” Gurganus said.

LiDAR is being adopted rapidly. Industry and highway agencies are trying to determine the best way to use it. There are three different types of LiDAR data. There is traditional terrestrial LiDAR used for static purposes. The laser is placed on a tripod and used for surveying. It is typically extremely accurate and can help develop accurate visualization of structures.

Mobile LiDAR is what TTI is using. It is mounted to a truck, boat or ATV. Mobile LiDAR provides lots of information that allows users to make good engineering decisions. Because it is mobile, it is not survey grade unless some additional steps, such as benchmarks, are included. For mobile LiDAR, one has to decide whether the data is being used to reach an engineering decision or for detailed design plans.

Airborne LiDAR mounted on drones or airplanes is used for broad mapping. It was seen in action on a recent television show where an overgrown area was surveyed to see if the contours of a man-made structure could be detected, even though the site was buried.

The hardware that is mounted on TTI’s trucks is mostly off-the-shelf equipment. The technology is a single boom-mounted laser device mounted 10 ft in the air. TTI uses a German-manufactured laser with a software suite developed by the Finnish company Roadscanners. It contains a 3-D accelerometer known as an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU). IMUs have been common in the aviation industry for years. A video camera captures images that can be matched to the GPS data. An industrial on-board computer is used to store the initial data. Data is then transferred to a removable terabyte external drive.

Utilizing LiDAR technology, researchers are able to collect extensive roadway geometric data, including roadway cross slopes, super elevations, front slope steepness and drainage areas on a roadway. A quarter-million data points are derived per one-tenth of a mile.

TTI recently purchased an additional truck and equipment to expand it capabilities. The turnkey cost of the system was approximately $140,000.

Gurganus hopes to link road distress problems to the collected data. “We know this roadway is having performance problems from a distress standpoint. How does that relate to ditch depth and offset? If a roadway is performing poorly, such as alligator cracking or rutting, we can now show that it has a shallow ditch close to the pavement’s edge. If repairs are going to be made, we can deepen the ditch and move it away from the pavement. It’s a more holistic repair approach,” he said. This gives highway agencies an entirely new data set to have a better understanding of the behavior or health from right-of-way line to right-of-way line.

The challenge is the amount of data LiDAR produces. In mobile use, it produces 250,000 points per tenth of a mile. The ability to store the data and access it is still evolving. As Gurganus noted, “It’s how to go from being data rich to being information rich. How do we supply the client with information-rich data that meets their needs?” Unlike the equipment, there is a scarcity of off-the-shelf post-processing applications to digest all that information. Each manufacturer supplies software with their equipment. TTI has had to create tailor-made software to successfully manage data related to surface drainage and hydroplaning.

A recent project in south Texas highlights the value of the LiDAR holistic approach. A section of roadway was being patched almost weekly. Based on a LiDAR survey, TTI recommended a full-ditch grading plan to fix the issues. If drainage water is flowing deep enough, water infiltration to the pavement can be stopped. The contractor is actively working on the drainage plan. “Maintenance departments want to immediately go in and do something to the pavement, and assume it will solve their problems. They’ve been doing something on a particular stretch of pavement for 10 or 15 years, but the problems remain. We want to make sure that drainage works properly before we fix anything related to the pavement,” Gurganus said.

Gurganus is excited about the possibility of using LiDAR data to predict roadway segments that might be susceptible to hydroplaning. “Hydroplaning is really a series of very unfortunate events that all take place at the same time. Only two are under the control of a state highway agency—the geometry of the surface and the texture of the pavement. There’s nothing that can be done when the posted limit is 65, it’s raining cats and dogs, and the motorist is travelling 72 and has bald tires. But with LiDAR data, agencies can identify geometry that might not provide optimum drainage conditions. This doesn’t mean that the agency has done anything wrong. Many of our roadways are 50, 60 or 70 years old. There are more cars, and people drive faster, so using LiDAR technology might help find vulnerable spots along the network,” he observed.

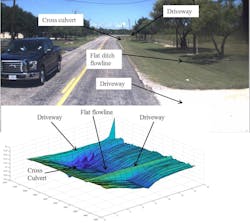

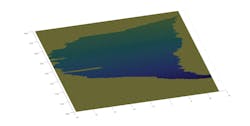

Gurganus has been gathering surface data and dividing it into 1-ft by 1-ft grids. This is a technique used to analyze large watersheds and drainage basins. Using LiDAR data, we are looking at much smaller drainage basins. Using these grids, we can look at water falling on the pavement surface and then build drainage basins along a pavement. Researchers can find the spots where water is running and where it will become the thickest. The thick spots are the critical locations for hydroplaning potential.

LiDAR measured the drainage basin along 400 ft of roadway with two lanes in each direction and a continuous left-turn lane. The LiDAR data was converted into 1-ft by 1-ft grids to map the drainage basin. Knowing the drainage basin allows researchers to calculate the water film thickness based on actual field conditions, rather than using design geometry.

Gurganus said, “I looked at a couple of equations that have been developed for hydroplaning speed. I ran simulations based on different vehicle characteristics. I can produce a hydroplaning potential speed. That allows the manager of that section of roadway to look at this hydroplaning potential speed and compare it to the posted speed limit, and make a decision based on the risk of hydroplaning on that roadway section.”

The next step is to validate these simulations. If the LiDAR data is proven to be reliable, changes can be made to the roadway or other engineering measures can be installed. At times, it will be difficult to adjust roadway geometry, but an agency might consider constructing a new surface with more macrotexture applied. Macrotextures create more water storage before water begins to build up under tires. This could mitigate hydroplaning. Gurganus thinks that this will become a major growth area for Mobile LiDAR technology.

Highway agencies also are extremely interested in using Mobile LiDAR to accurately measure vertical clearances for any overhead structures. It is far easier and safer to use LiDAR instead of a rod and level, which requires costly traffic control. By inverting the LiDAR unit, bridge clearance heights can be measured at highway speed. A highway agency manager said that it would save his district over $500,000 yearly in traffic control alone.

He continued, “If we can begin to integrate this information into project development, it will give transportation agencies more information so that their project scopes can be more refined. This should help them stretch their funds farther and do more lane-miles of work every year. Maintenance supervisors will be able to focus on problem spots with measurable data. Time, effort, materials and money will impact roads that really need it.”

About The Author: Dennis is senior communications specialist for the Texas A&M Transportation Institute.