By: Allen Zeyher

The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway is a good example of the kind

of work Slattery Skanska excels at. The contract, for the New York State DOT

(NYSDOT), calls for rehabilitating 2 miles of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway

(BQE) from the Broadway exit to 25th Avenue in Queens. It is big. It is

complicated. And it is in an urban area.

The contract is the largest NYSDOT has ever

awarded--$230 million--and involves reconstructing and resurfacing

roads and ramps, demolishing 19 bridges and building 17 new ones (15 road

bridges and two railroad bridges), reconstructing the connector from the BQE to

the Grand Central Parkway, widening lanes and changing alignments to reduce

curvature.

The bridge types include conventional wide flange beam,

prestressed concrete girder and box beam, trapezoidal steel girder and steel

truss.

Underpinning & Foundation Constructors Inc., a Slattery

Skanska subsidiary, is drilling augered soldier piles, cast-in-place concrete

pipe piles and miscellaneous timber piles.

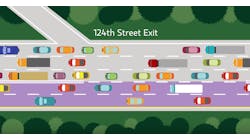

Like many clients nowadays, NYSDOT required that all lanes

remain open during rush hour, an additional challenge when the section of

highway under construction is one of the busiest in the U.S.

The BQE rehab work started in February 2000 and is scheduled

to be completed in June 2004.

Large, complicated jobs like BQE give Slattery Skanska a

chance to develop innovative solutions to engineering, logistical and

construction challenges. BQE is not a design-build project, but the

design-build strategy may present those challenges in a way that provides

especially fertile ground for innovation.

Slattery Skanska's first design-build project was

another highway construction project: the New Jersey Turnpike Exit 13A

Interchange in Elizabeth, N.J.

"What happens in the [design-build] process is that

the contractor brings means and methods prior to the bid, and the owner can

benefit from the means and methods that the contractor comes up with and is

actually incorporated in the price," Salvatore "Sal" Mancini,

president and CEO of Slattery Skanska and president of Skanska USA Civil, told

Roads & Bridges.

In the competitive bid process, on the other hand, the

contractor does not have an incentive to give away such proprietary means and

methods.

Slattery Skanska formed a design-build group in 2001 to

focus on this construction strategy.

Mancini said the design-build method was best employed in

situations where the new structure is independent of any existing structure:

"Then I think a contractor can have more control."

Slattery Skanska recently finished design-build construction

of maintenance facilities for Amtrak's high-speed Acela trains. The three

maintenance shops were relatively independent of the rest of the operating

system. Mancini commented, "We were able to come up with some innovative

construction techniques."

Building on growth

Slattery Skanska recently celebrated its 75th anniversary as

a company. It started as Slattery Contracting Co. Inc. in New York City in

1926. Its founder, James M. Slattery, led the company through the early days, building

a reputation for reliability and efficiency in the area of heavy civil and

mechanical projects.

The company really took off during the economic boom after

World War II, excavating and constructing foundations for some of

Manhattan's most prominent buildings, including the United Nations,

Seagram, Citicorp, Time & Life and Socony Mobil buildings.

Slattery entered the highway construction business in the

1950s with projects such as the Cross-Bronx Expressway, the Major Deegan

Expressway, the Long Island Expressway and parts of the Connecticut Turnpike.

Slattery constructed the approaches on both ends of the Verrazano-Narrows

Bridge and contributed work on the Gowans Expressway and the Brooklyn-Queens

Expressway Interchange. Slattery Associates won a contract in 1969 to construct

the Bruckner Highway Interchange in the Bronx for a total of $68 million, then

the largest single highway contract ever awarded by New York state.

It also was in the 1960s that Slattery constructed the

foundations for the World Trade Center in downtown Manhattan. Slattery expanded

into the mass transit construction business in the 1970s and 1980s. Among the

structures the company built were the L'Enfant Plaza Station in

Washington, D.C., Five Points Station in Atlanta, the 59th Street and Lexington

Avenue Subway Station and the East River railroad tunnel in New York.

Slattery consistently grew, even through tough years for the

economy. In 1989, the company was bought by Skanska USA Inc. In 1997, it

changed its name to Slattery Skanska Inc.

Slattery Skanska is an operating unit of Skanska USA Civil,

which had 2001 revenues of $1.46 billion. Skanska USA also encompasses Skanska

USA Building and Beers Skanska as well as Skanska USA Civil. Together, Skanska

USA had 2001 revenues of $6.674 billion, making it the third largest

construction company in the U.S. Skanska USA's parent company is Skanska

AB, based in Stockholm, Sweden.

In current projects, Slattery Skanska, with joint venture

partner Tutor-Saliba, is working on a $550 million design-build effort to

extend the Bay Area Rapid Transit to San Francisco International Airport.

Slattery Skanska is participating in joint ventures on nearly $1 billion worth

of work on "The Big Dig" in Boston. The company also has an $83

million contract to reconstruct the Times Square Subway Station, the busiest

subway station in New York City.

A few years ago, Slattery Skanska led deck rehabilitation

and power service conduit repair on the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge in New York

City. The project involved a full deck replacement with a latex concrete

overlay and a major upgrade of the electrical utilities.

Thinning margins

Skanska USA Civil is developing more of an emphasis on

construction jobs in niche markets. Highways and bridges are still a big part

of the company's output, but some other areas, such as mass transit, jobs

in urban areas and electric power generation, are yielding higher profit

margins.

"There are a lot more contractors in the highway

business, performing highways throughout the country," Mancini said,

"and I've experienced that the margins are very tight and very

tough going, even though we do indulge in some highway work here in New York

City and elsewhere. But I find that there are other niches that we've

gotten ourselves into that are much more preferable to us."

The latest statistics on states that face budget shortfalls

are not encouraging, either, for state-funded road and bridge work.

Skanska USA Civil does work in roadway, mass transit,

bridge, environmental and power generation construction.

International influence

Mancini said Slattery Skanska's parent has been very

supportive since the acquisition but not very intrusive: "It was an

amazingly smooth transition. There is no change in management. No one was

planted in Slattery to administer or change any of our management techniques or

our management processes."

At the time of the purchase, Slattery had annual revenues of

about $125 million. In 2001, the company brought in about $750 million.

The main benefit to Slattery has been the ability to bond

larger projects with the backing of the international corporation.

Having a European parent also may bring a somewhat different

sensibility down to the jobsite. With the full support of its Swedish parent,

Skanska USA recently became the first U.S. construction organization to achieve

ISO 14001 registration.

"It is a process of constant improvement in the

management of environmental resources," said Mancini. "We recycle

materials. Any site considered contaminated, we have a process on how to

address it. We are very concerned about the environment and how it's

treated and how we deal with it on a project site on all our projects.

"In Europe, this process is much more in the forefront

than it is here in the U.S.," he added. "It was very much supported

by our parent company in Europe as the thing to do."