By: Jim Kinder, P.E.

"I love the new interchange from I-470 to I-435. It runs so smoothly; it’s hard to imagine the traffic backing up as before. It allows me to leave for work 15 minutes later. Thanks for the hard work!"

—K. Witt/Kansas City-area resident

It has been called Kansas City’s Bermuda Triangle—a tangled mess of traffic where motorists’ patience disappeared into a sea of bumpers and tail lights. It is the area locally known as the Triangle. And, to the delight of the more than 250,000 commuters who brave its congestion daily, the Triangle itself is set to disappear within the next year when the old interchange is replaced with a $260 million redesign.

The Triangle’s reconstruction is the second-largest project the Missouri Department of Transportation (MoDOT) has ever undertaken in Kansas City. Nine years in the making, it promises motorists a host of benefits, some of which already are being realized. Among them: an estimated 360 fewer accidents a year, fluid movements and a new intelligent transportation system.

Safer, smoother, smarter. That’s MoDOT’s goal.

The three-sided monster

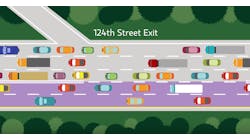

The Triangle is a convergence of I-470, I-435, U.S. 71 Highway and at least seven local routes, which form a notorious knot or triangle of congestion. For an idea of just how bad it was, most interchanges of two interstates are composed of 12 movements. The Triangle had 64. It was a Frankenstein’s monster of infrastructure built in disparate pieces during a 20-year period beginning in 1963.

Designed to accommodate no more than 180,000 vehicles a day, the Triangle had outlived its purpose and its capacity.

“Capacity coming into the Triangle was three lanes in every direction. Most places through the Triangle, except for mainline I-435, were either two lanes or one lane,” said Steve Porter, MoDOT senior community relations specialist.

While the Triangle was evolving, an event occurred that significantly added to its volumes. Bruce R. Watkins Drive, a project that would have been the city’s main north-south artery, stalled. Subsequently, growth of the bedroom communities east and west of the city kicked into overdrive. Commuters from those communities began feeding into I-470 and I-435. As a result, the east-west movement of the Triangle conceived as merely a feeder ramp system quickly became an overloaded east-west mainline. Once the completed Watkins Drive began funneling traffic into the Triangle in the mid-1990s, capacity reached a breaking point. Soon, the Triangle had the highest accident rate in the region.

One of its most dangerous movements was driving south on the Bannister Road ramp to I-435 with the intention of taking the ramp southbound to 71 Highway. Here, motorists were required to weave through two lanes of high-speed traffic to reach the far-left exit lane. To make matters worse, it was a one-lane exit and, as such, would routinely back up and come to a standstill on the I-435 mainline. The bottleneck caused everything from rear-end collisions and sideswipes to deadly accidents.

When MoDOT hired HNTB Corp. in October 1998 to redesign the Triangle, the project team was tasked with untangling the monster interchange.

Improvements in phases

Originally, the redesign had four phases. The project was extended to a fifth phase after hitting a funding snag in 2002. Phasing let the team target the Triangle’s worst problems first. That way, motorists did not have to wait until the project was complete to see progress. Following is a breakdown of the five phases:

Phase 1: Building a two-lane, south-to-west mainline on I-435; reconfiguring south I-435 ramps to south 71 Highway and east I-470 to separate express traffic; adding lanes to north I-435; and replacing bridges.

Phase 2: Building a new westbound I-470 and connecting ramps to northbound 71 Highway and I-435; and shifting westbound I-470 to the right side of 71 Highway.

Phase 3: Building eastbound I-470 and connecting ramps to I-435 and 71 Highway; constructing most of the ramps north of Red Bridge Road; and building ramps from south I-435 to south 71 Highway and eastbound I-470.

Phase 4: Building the remaining connecting ramps at I-435 and 71 Highway and I-470 interchanges; constructing Red Bridge Road; and building service roads between Red Bridge Road and Blue Ridge Boulevard.

Phase 5: The current phase is the most difficult and congested stage of the redesign. Construction began in January 2007 and continues on 71 Highway from Red Bridge Road to Blue Ridge Road. MoDOT completed the outer roads along 71 Highway this past year. In February, MoDOT shifted traffic onto those outer roads so that it could remove, realign and replace mainline 71 Highway’s pavement.

“The [original] pavement on 71 Highway was laid the year my sister graduated from high school,” Porter said. “She retired last year.”

The 44-year-old pavement is composed of 4 in. of aggregate topped with 9 in. of concrete and rebar. Its limestone aggregate base is now the consistency of toothpaste.

Most of the new lanes, built to last between 40 and 50 years, feature 14-in. pavement on top of an 18-in. rock base. In addition to new pavement, the 18-month phase involves replacing the Longview Road underpass with a bridge over 71 Highway and final ramp connections to Red Bridge Road and Blue Ridge Boulevard.

The result will be three continuous lanes with minimal merging. And, for the first time in 20 years, 71 Highway will be the dominant corridor of the interchange.

This spring, four of the five phases will be complete, the fifth phase will be under way, the last of 30 old bridges will have been removed and the last new bridge will be under construction. By winter, and for the first time ever, all capacity that moves into the interchange will be adequately accommodated.

From challenge comes achievement

That is how far the reconstruction has come, but progress is only half the story. Why it has worked so well also is worth noting. The two greatest challenges, maintaining existing traffic flow and never straying from the original sequencing, became two of the team’s greatest achievements.

During construction, MoDOT was committed to keeping all lanes open from 6-9 a.m. and 4-8 p.m. Monday through Friday. Until the redesign, maintaining existing traffic flow typically meant keeping at least one lane open. The Triangle project redefined “open.” The entire interchange was designed and construction was sequenced to allow for maintaining the same number of lanes as existed before construction started during peak hours. Also, the contractor was permitted to close lanes only during predetermined off-peak hours or pay a $6,000-per-hour fine.

“Reconstructing the Triangle while maintaining traffic was like rebuilding a 40-story office building with the people still working in it,” Porter said. “It was a stunning accomplishment.”

The second success: The project’s entire sequence was outlined in 1999, and it has not changed throughout the six years of construction. Three factors fostered that consistency.

First, the sequencing required minimal project overlap. Contractors could get their jobs done and get out of each other’s way. When projects did overlap, MoDOT added incentives to encourage contractors to finish before letting the next job. Contractors worked at night and during off-peak hours to maintain their schedules, and when they beat their deadlines, they received the incentive then rather than at the project’s completion. If contractors did not meet their deadlines, they were fined $8,000 a day.

Even though the redesign was a traditional design-bid-build project, it worked much like a design-build. One piece of the project would be designed, let for construction, and while it was being built, design would be under way for the next piece. If the entire interchange had been designed all at once, the design time alone would have taken four years. To build it would have taken another seven. Using the design-build-like approach, the project team shaved two years off the project’s schedule. And, in the six years since construction began, the project has not experienced any downtime.

Third, MoDOT was able to secure funding when it was needed, despite the failure of Proposition B in 2002, which would have increased the state’s gas tax by four cents per gallon. The unexpected defeat affected funding of the Triangle’s redesign significantly, which led to the second-biggest challenge.

With phases one and two under construction, MoDOT asked the team to break up the remaining two phases into smaller pieces. Projects $50 million to $80 million in scope were broken up into $10 million and $15 million chunks, creating smaller phases and expanding the four-phased project into five. That was risky. Changing one step in a sequence could have had a domino effect on the entire redesign, knocking schedules and budgets out of alignment. Difficult as it was, the team completed the task, giving MoDOT the flexibility to let projects as funding became available.

Luckily, the passage of Missouri Amendment 3 in November 2004 helped solve the problem. It allowed MoDOT to use bonds to pay for projects that were already in the pipeline, assuring availability of the funds needed to complete the redesign on time.

As a result of the sequencing, the design-build-like approach and steady funding, jobs often were completed on or ahead of schedule, allowing MoDOT to announce a major improvement each fall:

- Spring 2001: Construction began;

- Fall 2002: Southbound I-435 opened;

- Fall 2003: Westbound I-470 opened;

- Summer 2004: Northbound I-435 opened (ahead of schedule);

- Fall 2005: Eastbound I-470 opened;

- Fall 2006: Red Bridge Road opened; and

- Fall 2007: U.S. 71 Highway will open, completing 99% of the project.

“HNTB deserves a lot of the credit for maintaining traffic and delivering something each step of the way,” Porter said.

Safer, smoother, smarter . . . satisfied

MoDOT plans a grand opening ceremony late this year. At that time, the old Triangle will vanish forever and the new Three Trails Crossing Memorial Highway officially will take its place. The new interchange will accommodate traffic volumes into 2020 of more than 400,000 vehicles per day.

Named for the convergence of the historic California, Santa Fe and Oregon Trails, Three Trails will be built to 30-year durability standards, 50% longer lasting than previous highway construction standards. For motorists, that will mean less intrusive and less frequent maintenance work. Plus, the new system is designed in such a way that if MoDOT wanted to add another lane in the future, it could without rebuilding the entire interchange.

In the meantime, speeds are up and the number of accidents is down. And, motorists are loving it. It seems MoDOT’s goal of a safer, smoother, smarter interchange is becoming a reality before the redesign is even finished.

Safer

The number of accidents already has diminished, bringing MoDOT closer to its goal of preventing nearly one accident a day.

“The restructuring of the Triangle’s most accident-prone area was absolutely the right design,” Porter said.

Smoother

Traffic flow is smoother. In July 2005, eastbound I-435 pavement loops located just west of the Triangle indicated peak rush-hour weekday traffic averaged a frustrating speed of only 22.7 mph. Now that new eastbound I-435 lanes are open, the average speed during afternoon rush hour is 51.9 mph.

Smarter

The interchange now is monitored by Kansas City Scout, the metropolitan area’s intelligent transportation system. Scout incorporates video cameras, vehicle sensors, electronic sign boards and other devices to monitor traffic and inform drivers of problems ahead, giving them information about delays and, in many cases, the option to choose another route.

Satisfied

"There’s one more word MoDOT may want to add to its trinity of safer, smoother, smarter. That word is “satisfied” as the department continues to receive e-mails from delighted motorists . . .

. . . you guys should be congratulated . . . what an achievement . . . and what an improvement and without closing access in any direction! Hats off!"

—P. Hodes/Kansas City-area resident

About The Author: Kinder, senior project manager for HNTB Corp., has served as project manager on the Triangle redesign since its inception in October 1998. He can be reached at [email protected] or at 816/527-2282.