The I-59/I-20 Corridor, the largest project in the history of Birmingham, Ala., looks to reinvent the city’s business district

By: Brian W. Budzynski

Along with being one of the most sizable and significant banking centers in the nation, Alabama’s largest city is also a primary hub for rail development and freight movement, medical care, and the insurance industry.

Unfortunately, the city’s Central Business District (CBD) has been unable to keep up with what is otherwise a progressive social and economic locale. Soon, however, this will no longer be the case.

The Alabama DOT (ALDOT) has initiated the reconstruction of the I-59/I-20 Interchange in the CBD as part of a larger reinvention of the downtown area into a 24-hour mixed-use district. This $750 million megaproject is by far the most ambitious piece of construction the city has seen, and it is one that has city officials and ALDOT alike looking forward to a reduction in traffic congestion, improvement in overall mobility, and a fresh new thrush of growth for small businesses and the city’s evergreen industries.

But while the physical renovation of this area, which is presently deep into its largest and final phase, makes for impressive viewing, it all began in the smaller aperture of a computer screen.

Crews building the main 59/20 bridges.

2.3 BILLION POINTS OF LIDAR

The city of Birmingham has been in something of an extended growth spurt for several years now. Since the 1960s, population has surged by more than 1.1 million souls, yet the city’s infrastructure has not kept up with the commensurate demands of such expansion. The I-59/I-20 corridor was designed to match the 60,000 vehicles per day that were then using it; that number today is closer to 160,000, and is projected to reach 225,000 by 2035. Added to which, access is, frankly, bad. The locals know it as “Malfunction Junction.” There exist odd left-hand on- and off-ramps as well as weaves that have resulted in high accident and collision rates.

Among the first tasks for design firm Volkert Inc. was to envision not merely a correction of existing ineffective design elements, but a wholly new conceptualization for what the interchange would mean both to development in the greater business district and correction of economic disparity concerns that have resulted from the corridor’s original construction.

“The right-of-way wasn’t very significant for a project of this size,” Drew Davis, P.E., ENV SP, assistant vice president for Volkert, told Roads & Bridges. “Pretty much everything we planned was within the existing right-of-way. There are some environmental justice issues surrounding parts of the project area, isolated neighborhoods and so forth, which made it important to minimize right-of-way acquisition. The CBD divides commercial locations with a residential area to the north. In fact, it was a big issue in the 1970s, how it split the city like that.”

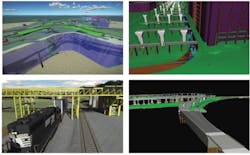

Consequently, a comprehensive survey and evaluation of the area was performed in advance of the involvement of ALDOT’s Design Bureau Visualization Group, which was tasked with coordinating information exchange among multiple offices and utilities, as well as communicating with the public and stakeholders to quickly deliver an accurate 3-D model that could be used to complete construction within 14 months.

“There was an extensive soil survey done,” Davis said. “A boring at every footing location with four to five geotechnical consultants helping out. That boring log eventually was turned into solid layers in the 3-D model. There was about every utility you can imagine impacted on this project’s limits. Telecom, buried electric, a 115-kv oil-cooled static line that was crucial to avoid, water, sewer, overhead power, overhead telecom on one bridge that needed supporting. It was very comprehensive.”

Heading the 3-D model efforts was Visualization Engineer Matt Taylor: “Birmingham is an old city, but luckily we were able to get as much data as we could. The 3-D model helped us work out a few issues before we even began, such as foundation locations in relation to utilities, proposed storm drainage, and footing exposure—that was probably the biggest one. That would have been a pretty big delay, if it had made it to the planning stage, but we caught it and dealt with it first.”

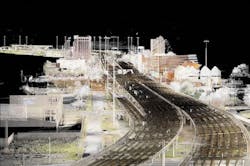

More than 2 billion individual points of LiDAR were captured in the course of pre-model surveying in order to create the eventual 3-D model.

A 14-month shutdown is nothing to blink at, so both Volkert and Taylor’s teams knew it was crucial to both do diligence to the needs of design and to also keep the citizens of Birmingham directly in the loop as to the scope and promised results of the project.

“First we had to make an existing conditions model,” Taylor said. “We took a ton of LiDAR—2.3 billion points, something like 80 gigs of files. We had so much data to work with. We partnered with Land-Air Surveying Co. to build our initial model in Bentley MicroStation using Descartes v8i. That was everything, ground and up. Using a clash detection feature enabled 1,000 interferences to be identified and resolved prior to construction. This resulted in more than $10 million in savings. We also needed to make sure everything cleared the utilities, so we made a 3-D underground model of the utilities, for which we took a lot of subsurface data. The design helped us tremendously to make the model. We were able to use ProjectWise to collaborate our data together with Volkert, and also to loop in all parties. We managed to do that really fast, actually, and we saved an estimated $40,000 in man-hours, along with $50,000 in printing costs. As soon as Volkert completed a piece of the project design, they sent it to us and we integrated it into the 3-D architecture. There were a lot of businesses interested in this project, so the model was very useful in that regard, too. Whenever we needed to approach a member of government or a business owner, this aided us very much in showing them exactly what it would be like.”

Buy-in is a crucial and often undervalued aspect of project development, but Taylor’s group was able to leverage their software to, in essence, create a simple package that any potential stakeholder could easily understand.

“We used LumenRT to create a live cube,” Taylor said. Think of it as a short-form video game interface, one in which you can explore an entire environment, from a bird’s-eye view down to the subtlest detail of color distinction, and even ‘take a ride’ through the environment as an actual road user might. “We put every aspect of the model into the live cube, which made it extremely easy to navigate when we would do a virtual demonstration.”

This model would continue to aid crews as the project left the design phase and began to break ground. What’s more, it forged a new path of interest for ALDOT.

“Our administrators love this,” Taylor said. “They fully intend to keep using 3-D modeling. It aided right-of-way permitting and smoothed the path to construction. This was the biggest project ALDOT has ever done and it’s on our busiest corridor. The 3-D model helped us stay on schedule.”

And when $750 million is on the line, the schedule is everything.

Within MicroStation and other software interfaces, ALDOT visualization engineers were able to break each aspect of the proposed project site down to the most minute detail.

IN WORKING ORDER

Site conditions when boots finally hit the ground held up ALDOT’s decision to accomplish this project in as quick a timespan as possible.

“Bridges were deteriorating,” Taylor said. “We had to put up fencing around all the bridges in the area for public safety to contain falling concrete.”

The construction phase was broken up into four phases. Phase A, completed first, saw the reconstruction of the 12th Avenue North and 31st Street North Bridges, as well as retaining wall and minor ramp and roadway work. The next phase, known officially as Phase 1, widened several existing bridges on I-65 over 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Avenues North in advance of capacity increases on the main thrust of the project zone coming in from the south, as well as a pair of bridge jackings to boost clearance. Phase 2, which opened in October of last year, was comprised of the reconstruction of the I-65 and I-59/20 Interchange ramps, which had to be in place in order to begin removal of the segmental bridge area—leading into the most significant portion of the overall project, Phase 3.

Beginning in March 2017 with an expected completion date of 2020, Phase 3 will see the erection of the mainline bridges, which will employ, in different areas, both precast concrete segments and steel girders supported on cast-in-place concrete piers.

“The two CBD bridges, as we call them, on mainline I-59/20, are each 1.25 miles long and precast segmental construction from beginning to end,” Skip Powe, P.E., state construction engineer for the Alabama DOT, told Roads & Bridges. “The other bridges we’re doing leading off of that are either traditional concrete or steel girders. It’s a question really of radius and how tight some of those curves are. If it’s a sharp radius section, we’re doing steel. Of course, in some areas on the ramps you’ll begin with concrete and then hit an area where that curve radius tightens and then boom, we’re moving to steel.”

All told, crews will place 2,316 precast concrete bridge sections. Each of these sections have been cast in a yard located just 1.5 miles from the project site, which has leant project planners the advantage inherent in all precast activities—a high level of quality control—as well as a limited freight requirement in getting materials to various points on the project site, which has led to time and cost savings. On a project with 65.5 lane miles and 31 total bridges, every minute of every working day counts. “It’s certainly made for a convenient transfer of these segments,” Adam Patterson, project manager for Volkert, told Roads & Bridges on our visit to this project in March 2019. “We have multiple casting beds in place, which has made the process quite smooth and efficient. And segmental is fairly quiet, so we can reduce the noise aspect of building the bridges.”

ALDOT has been in the thick of construction for some time, and the reliability of the accumulated survey data and pre-construction modeling has shown significant benefits. “I’ll tell you, it made a huge difference on the front end knowing where a lot of our underground problems were,” Powe said. “We were much better prepared than otherwise.”

Of course, as any contractor or agency knows all too well, every project has its little peccadilloes. “It’s an urban job, so there are, of course, unknowns,” Powe said. “For example, you go out there and find a manhole where there wasn’t supposed to be one, or you pull the lid off of one you knew about and find that it’s collapsed somewhere along the way. But we’re in a better spot certainly because of the clash detection surveys and UAS photography we did in the design stage and incorporated with traditional 2-D plans.”

Demolition of the old structures in advance of the full interchange shutdown. Photo courtesy of Alabama DOT.

LOOKING FORWARD

“The contracted completion date overall is November 2020,” Powe said. “For the CBD bridges the closure timeframe is 14 months. This is where is gets a bit tricky. The contract was built so that if the contractor can complete the mainline bridges by mid-March, then they’ll have about seven months to take care of some other work we can’t really do until those bridges are up. They can earn a full bonus on the bridges if they come in by Martin Luther King Day of 2020. There’s an LED lighting system that is going in underneath the bridges, so the city can then go in and perform its beautification program.”

City leaders have approved a planned CityWalk underneath the corridor that will include walking paths, playgrounds, a dog park, space for a farmers’ market and cafes, and a music venue.

“There’s also a culvert that runs underneath the Birmingham–Jefferson Convention Complex (BJCC),” Powe added, “adjacent to the project site, which backs up in heavy rains and floods the basement of the BJCC. During the design stage, the city made ALDOT aware of this problem as well as concerns for post-construction runoff. As a result, a new culvert was designed and included with the plans for all the bridge work. It runs from the east end of the project to the west and ties into the existing structure that discharges into a local tributary and will provide better drainage through CBD. Due to the sequencing of the project, only some of the culvert could be installed prior to the construction of the CBD bridges. One of the big challenges to add this culvert was that the geology of downtown Birmingham is rock. We are having to blast down 15-20 ft next to existing buildings and adjacent to utilities like the oil-cooled static line to install it. So, the remainder of the culvert installation along with the LED lighting system is why the contract completion is November 2020. If the contractor can come in [on the bridges] by MLK Day of 2020, that would give them nearly nine months to wrap up the lighting and culvert work on the backend. Sure, it’ll cost ALDOT more money, but when you put in that kind of incentive and you’ve got the kind of traffic we have down here, it’s worth it. It’s a win-win for everybody. Simple as that.”

When all is said and done, more than 2,300 precast bridge segments will be erected.

About The Author: Budzynski is managing editor of Roads & Bridges.