By: Amy Northcutt

Government agencies are under pressure to optimize limited resources while also responding to increasing demands for better performance. Across the country, deficient bridges are a growing problem. The U.S. has 614,387 bridges, almost four in 10 of which are 50 years or older. More than 54,000 bridges of those bridges need to be repaired or replaced. These factors earned U.S. bridges a C+ score on the ASCE’s most recent infrastructure report card. While the private sector has overcome similar pressures with building information modeling (BIM), the public sector is working toward its own digital transformation and exploring the opportunities that come with technology in bridge design, construction, and asset management.

In 2018, the Iowa DOT kicked off a Transportation Pooled Fund Project to advance open data standards for BIM for bridges, also known as BrIM. Interested in the value BIM can bring to bridge projects, 15 DOTs signed on to participate and, along with other experts participating in the project, shared their take on BrIM and what they see as the path to adoption.

Changing culture

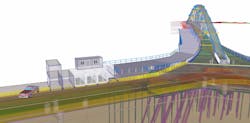

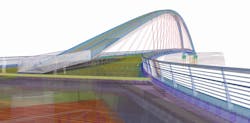

From planning to design, construction, and asset management, BrIM comes with a long list of benefits. Data-rich constructible models boost design quality with up-to-date information and consistent documentation. BrIM allows for accurate pre-fabrication, just-in-time material deliveries, and project collaboration across disciplines.

Several DOTs are already exploring BrIM on pilot projects, while others are just beginning to understand 3D modeling. It is important to note that all not all 3D modeling software solutions are equal to BrIM. BrIM goes beyond basic 3D objects and emphasizes the “I” in the middle, accumulating a high level of detail and data in the model during design and construction so that it is useful throughout the entire lifecycle of the bridge. Regardless of where they are on the path to adoption, most DOTs agree that BrIM is the future, and although change is hard, it’s worth the effort.

While the technology is available today, many see the greatest challenge as cultural change across institutions that are comfortable with the current way of doing business.

Elias Kurani, chief of the Office of Bridge Design Central for the California DOT (Caltrans) agrees that adoption will require DOTs to step outside of their comfort zones. “2D has been the norm for a long time, but we see the value that 3D models bring in visualization, accuracy, and transparent communication between disciplines,” said Kurani. “BrIM is going to be a big part of the industry moving forward and we have to adapt.”

This digital transformation and move toward constructible BrIM will hold even greater importance as the number of digital natives moving into the workforce grows. Francesca Maier, a principal consultant with Fair Cape Consulting and participant in the Transportation Pooled Fund Project, sees technology adoption as a critical part of attracting talent today and in the future. “Younger engineers have expectations for digital workflows and the industry isn’t going to attract and retain those professionals with 2D,” said Maier.

Utah DOT’s chief structural engineer and chair of the AASHTO Committee on Bridges and Structures, Carmen Swanwick, agrees that digital workflows will attract younger engineers. “Engineers coming out of college today don’t want to sit down behind a desk and draft plans on paper,” she said. “They want to work in the model, visualize their work, and collaborate with others. As an industry, we need to provide them opportunities that consider the advancement of technologies.”

Industry alignment and standardization are key to adoption

In addition to educating and driving cultural change, the DOTs involved in the Transportation Pooled Fund Project are developing standard definitions for U.S. bridge design and fabrication elements and aim to align on Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) as the industry’s open data exchange standard.

“Adoption is dependent on the ability to reliably exchange data through an open data standard,” said Maier, who sees IFC as a key driver of BrIM adoption. “If we’re locked into a proprietary data format, we can’t share the model. In that case, that data becomes siloed and the benefit of BrIM is minimized. Once we agree on IFC as the file format for bridges, vendors can create apps with reliable data exchange. I think at that point we will see the transformation as contractors realize, ‘I could really use that. It could simplify my work.’ For now, the construction side doesn’t really know how to use BIM for bridges, so we will continue to see the same old plan outputs.”

For Utah’s Swanwick, standardizing on classification system, regardless of software is equally important. “Today, the way we define a circular column in one project, may not be the same as defined in the next project as standards have not been established,” said Swanwick. “Before we can truly adopt BrIM, we need a classification system so that data is consistent as it is shared with stakeholders from one project to the next. We need to be consistent so that users know what to expect.”

Contracts will also be impacted by BrIM adoption, which is something that could be simplified by creating model-based reporting and contracting language that can be used by all DOTs.

The value in design, construction and beyond

As part of the model-based design and construction initiative launched in 2014, Utah’s DOT has already completed 10 roadway projects using 3D models and is currently completing a pilot for a major roadway reconstruct that includes three bridges. “Our pilot projects have gone very well,” said Swanwick. “With 3D and BrIM, the goals are to produce optimal designs and through the information transfer from design to construction and beyond, make better decisions and manage the entire bridge lifecycle from planning and design to construction and asset management.”

Handing over an as-built model including data that lives on after construction is complete and is utilized for asset management is seen by many DOTs as a long-term benefit of BrIM. For example, it can be used to provide safe routing and permitting for heavy trucks in automated fashion, which will improve the safety of the network and mobility of freight.

Extending BrIM to asset management eliminates the need to manually enter or transfer data on the health of bridges during in-service bridge inspections. “We aspire to use BrIM beyond construction so that in-service bridge inspectors can use a tablet to pull up the model onsite and automatically update the database with the bridge’s condition information in real-time,” said Swanwick.

The Future: What’s it look like and how do we get there?

Early adopters have already started to pave the way, but many envision BrIM taking hold gradually over the next decade. Utilizing model-based project management will make communication more transparent and enable collaboration regardless of project types. “I see us making an incremental transition toward model-based design, gradually improving efficiency and collaboration between project owners and stakeholders,” said Kurani. “At Caltrans, we still predominantly follow a traditional design-bid-build process. Contractors are comfortable with our current process, so they aren’t pushing us to implement BrIM. Yet, we have to advance technologically and drive the changes that will bring more efficiency, less waste, and better outcomes to our projects. Model-based design allows us to work far more efficiently and do more with the budget that we have.”

Others echo that BrIM is more effective in a design-build scenario because the stakeholders are all part of the same team and are motivated to work together, minimize errors, and deliver the project at maximum efficiency. As the model becomes an as-built record of the bridge, many think we will see the industry move even further towards collaborative projects.

Caltrans has its eye on BrIM and sees adding a BIM expert to its staff as a key first step to educating and getting people on board. “We are ready to push the envelope and doing our part to make BrIM more mainstream,” said Kurani. “We’re creating a culture shift, however basic it might be, and taking the steps to help engineers become familiar with BrIM so they can share that value with other stakeholders.”

Education continues to be a big part of moving the industry forward. “It’s going to require us to educate the owners on BrIM,” said Maier. “If you think about road design as an analogy, we’ve had the tools to design roads in a way that provides the information contractors need for machine control since the 1990s, but the contractors had to lobby the owners to ask for the data. The DOTs have been very focused on construction handover and haven’t looked internally and said, ‘Look, we have zero automation in our plan production process.’ They’ve missed the fact that automation and 3D data have been used for roadway plan production for almost 30 years.”

With many DOTs unsure of where to start, Swanwick thinks evaluating current workflows and procedures to find areas, where one could work more efficiently with BrIM, is a good place to start. “Today, there is no manual for how to use BrIM, but it will become easier to roll out as the industry works together to develop standards and address the challenges and opportunities that BrIM brings to project workflows and project delivery stages. DOTs can’t do this in a vacuum. It requires buy-in from consultants and contractors. We need the entire industry to embrace BrIM to get the biggest benefit.”

About The Author: Northcutt is Senior Technical Consultant, Engineering with Trimble.