By: Ed Hernandez

When people think of New York City’s bridges, they often think of the iconic East River bridges like the gothic-inspired Brooklyn Bridge or the steel latticework of the Queensboro Bridge.

But the overwhelming majority of New York City’s 2,000+ bridges are actually much smaller and often hiding in plain sight. They have been woven into the fabric of streetscapes and neighborhoods as the city has developed over and around them.

Despite their ubiquity, the average New Yorker would be hard pressed to name 10 of these roadway bridges, much less keep track of them all. It is, however, the New York City Department of Transportation’s (NYCDOT) responsibility to keep track of 794 of these bridges, and make sure that they are safe and in good working order. It is NYCDOT’s responsibility to plan for the reconstruction of these bridges, so that funding becomes available just as an old bridge reaches the end of its useful life. NYCDOT relies on bridge condition ratings to forecast when these bridges will reach the end of their useful life. If a bridge is expected to reach a condition of “poor” in 2024, NYCDOT makes sure that funding is available for the design of that bridge in 2020, and that funding is available for its reconstruction no later than 2024. This planning method has worked for decades, particularly during an era when most of the bridge infrastructure was relatively young and needed few major overhauls. However, with a bridge portfolio composed of structures primarily built during the post-World War II era and nearing the end of their expected 70-year life, NYC is at the leading edge of a nationwide wave of bridge reconstruction needs. What’s more, this wave is worrisomely coupled with a persistent drought in infrastructure spending. What results is a condition for which the old methods of planning and prioritizing are no longer sufficient. A supplementary system for identifying and prioritizing the most vital and cost-effective bridges has become necessary.

An example of the difference between the length of an existing bridge (build route) and the shortest alternate route (no-build route).

Far from the back of an envelope

In order to create a screening tool that was more than a back-of-the-envelope calculation, yet not as time-consuming or costly as a full benefit-cost analysis, we identified the following qualities that it needed to possess:

- Ease of measurement—It had to be based on easily available data. This meant that NYCDOT could not incorporate traffic studies and traffic models that would take weeks to develop for each bridge;

- Uniform—The data used had to be apples-to-apples so that score results could be used to compare bridges to each other;

- Fact/data driven—The goal of the screening tool is to help decision makers and inform political decisions with facts and analysis. The tool itself should not take political factors into account;

- Incorporate agency strategic goals—NYCDOT is committed to the mobility of all users. As such, it was important that the screening tool incorporate travel-time benefits to cyclists and pedestrians, as well as vehicles. In addition, given NYCDOT’s commitment to Vision Zero, it also was important to factor safety into the tool; and

- Maximize benefits per dollar spent—The screening tool would provide results in a benefit-cost ratio format that would allow NYCDOT to compare an investment in one bridge versus another.

Neighborhood on 47th Street near 10th Avenue in the Hell’s Kitchen area of Manhattan.

World against world

As a general matter, the benefit-cost analysis that was performed compares a world with a bridge against a world without a bridge—build vs no-build.

Given the requirements above, NYCDOT developed a bridge-ranking system that incorporates:

1. Bridge performance—User counts (bicycles/pedestrians/vehicles) were performed on each bridge for 24 hours using digital video cameras and video processing by Miovision. This allowed NYCDOT to develop an Average Annual Daily Traffic quantity for each mode choice for each bridge. This was the costliest and most time-consuming portion of the analysis. However, due to technological advances it was far more affordable than manual counts (given the cost of labor in NYC) and far more accurate given that NYCDOT was able to use prime contractor (Henningson, Durham & Richardson Architecture and Engineering P.C.) to spot-check the counts using the stored video. Despite the time and cost, it was critical to accurately measure the number of users and their modes to accurately monetize the benefits produced by each bridge. These counts also provided a wealth of data on how bridges were being used.

2. Societal benefits—Travel-time savings for existing bridge users were calculated by using the number of cars, bikes and pedestrians currently utilizing the bridge, the average citywide speed of their mode of choice, and the difference between the length of the existing bridge (build route) and the length of the shortest alternate route available to them (no-build route). The convention that was used to determine the alternate (no-build) route is simplistic: It would always be the shortest possible (non-bridge) route between the two points at either end of the existing bridge. This methodology is a rough shortcut meant to provide a ballpark measure of the inconvenience created to users in the no-build scenario. It does not take into account potential traffic delays, as incorporating that level of modeling into each analysis would have been impossible to perform given the scale of this project. It also doesn’t take into account the various routes that users could realistically take to get from their origin to their destination. The convention overstates the alternate route distance (thus overstating benefits per bridge) while understating the potential traffic impacts of the bridge closure (thus understating benefits per bridge). Perhaps they cancel out. Without a traffic study and an origin destination study, it is difficult to determine. The travel-time savings were monetized and summed for the entire term of the structure’s expected useful life.

3. Safety benefits—The five-year injury history (both volume and severity) of the existing bridge route was compared to the five-year injury history of the alternate route. U.S. DOT methodology was used to monetize the safety benefits. This requires knowledge of the severity of injuries, not just the number injured, as the monetized benefits of avoiding a severe injury or death far outweigh the monetized benefits of a slight injury. This is an estimate of the value that society places on saving lives and the cost of treating injuries. The difference was then monetized and used as an indicator of the relative additional danger posed by the alternate route. It is important to note the roughness of this estimate. In the real world not all of the current bridge users would take the alternate route. There are many routes one could take other than the alternate route if the bridge were not to be reconstructed. But also, the measure doesn’t take into account the crash rate. In other words, how many more injuries can we expect for every additional car/pedestrian/cyclist on the alternate route? This information is simply not available as it would require historical knowledge of vehicular/pedestrian/cyclist volumes for all of the alternate routes. The hope is that in a more detailed study, the safety impacts can be studied with more precision. For immediate purposes, this measure is an approximation and works adequately to flag comparative safety between a bridge and its alternate route.

4. Environmental benefits/vehicle operating cost savings/pavement maintenance savings—Using the calculated vehicular AADT and the alternate bridge route distance, NYCDOT was able to estimate the amounts of greenhouse gasses avoided in vehicular emissions due to the presence of the bridge. This benefit also was monetized and calculated for the term of the structure’s expected life. Likewise, vehicle operating cost savings and pavement maintenance savings were calculated.

5. Cost—Developing a detailed cost estimate for each bridge would have been a daunting and time-consuming task. Instead of doing this, NYCDOT estimated bridge reconstruction costs by multiplying the deck area of each bridge by the five-year average cost of reconstruction per square foot of bridge deck.

View of the separated pathway for pedestrians and cyclists on the Brooklyn Bridge.

Benefit cost percentile: Using these simplified inputs, NYCDOT was able to produce benefit-cost ratios for every bridge which usage had measured (200 bridges to date). All of the inputs, other than the user counts, were easily available over the internet. Google Maps was used to measure alternate routes and distances, and deck sizes and safety profiles were available through in-house resources. The entire analysis was performed using Excel.

An important note on safety benefits: The safety benefits were not folded into the benefit-cost ratio, but were highlighted separately due to the importance of seeing these effects distinctly from the travel-time benefits. Therefore, the benefit-cost ratios were mostly representative of the travel-time savings (95%). Environmental benefits, vehicle operating cost savings and pavement maintenance savings only represented about 5% of monetized benefits when combined.

Once benefit-cost ratios were calculated for each bridge, the bridges were arranged by benefit-cost ratio from highest to lowest, and the lowest tenth percentile (20 bridges out of 200 studied) were flagged for further study regardless of whether their BCR was above or below 1.0 (the ratio at which benefits exceed costs). It is important to note that the absolute benefit-cost ratios are not used in and of themselves; the coarse assumptions about both benefits and costs would misrepresent the value of each project. But the relative ranking of projects by BCR is thought to be useful, as low-ranking projects are more likely to be less cost-effective and should receive greater scrutiny.

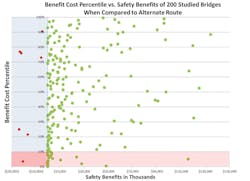

Results: Screening for economic value and safety impact: The results of the analysis can be plotted on a graph with the Benefit Cost Percentile on the y-axis and the Safety Benefit (in $ thousands) on the x-axis (see p 48). By displaying these results graphically we can see that most bridges are safer than their alternate routes—most are to the right of the y-axis. In fact, some (on the far right side) are much safer, which indicates that they are not only providing a travel-time benefit, but a substantial safety benefit to the users of the bridge and to the residents of the surrounding areas. However, if the bridge is too far to the right, it’s probably an indication that the alternate route is unusually injury prone and should probably be reviewed for safety. There also are a few bridges to the left of the y-axis, indicating the bridge is actually more injury prone than the alternate route. This lets us know that special attention must be given to the safety redesign of these bridges.

The shaded area in red highlights the area below the lowest tenth percentile. Bridges that are plotted in this area are flagged for further study. Surprisingly, there also is a bridge that is to the left of the y-axis and also in the red area below the tenth percentile. This means that the bridge may be both a poor investment (at its estimated cost) and injury prone (as compared to the alternate route). This bridge also will be flagged for further study and will be especially scrutinized. Bridges that are above the tenth percentile mark and to the right of the y-axis will not undergo additional economic analysis because they are both cost-effective and produce safety benefits. These bridges represent 87% of bridges screened by the tool.

The Carroll Street Bridge is a retractile bridge that spans the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn.

Implementation: Over the course of the past year, a joint task force from the Bridges Division, the Budget Division and the Commissioner’s Office reviewed the results of the analysis with a focus on those bridges in the bottom tenth percentile. It was determined that the metric was in fact accurately flagging bridges whose reconstruction costs did not appear to be justified given their current usage. For example, the benefit-cost screening tool correctly flagged the 216th Street Pedestrian Bridge in Queens, a bridge that engineers had previously flagged for demolition due to its poor usage and high reconstruction costs. It also flagged a bridge whose alternate route had been significantly shortened by the construction of a new bridge. Perhaps the old bridge doesn’t need to be reconstructed given the existence of the recently completed bridge. Only a full analysis could provide the information necessary to make a decision. Under the direction of agency leadership it was decided that these bridges would, in fact, undergo further scrutiny during design. These additional studies would address the weaknesses of the standardized method as they would evaluate likely detours and collect enough data to calculate crash rates for the detour routes. As part of this “enhanced design” requirement, NYCDOT will now request that preliminary design for these bridges also include the following:

- Traffic counts for all classes of users: autos, trucks, bicyclists, pedestrians;

- Analysis of a “no-build” alternative;

- Traffic analysis of alternate route, including the impact on response time by emergency services;

- Impact of relocating utilities such as gas, water and electric lines;

- Cost to remove the bridge;

- Cost of any required improvements on the alternate route;

- Safety analysis of the build and no-build alternatives, including crash rates;

- Design and analysis of a lower-cost alternative, potentially with lower capacity and a smaller size;

- Benefit-cost analysis of original and lower-cost alternative; and

- Land-use analysis.

Based on the results of these studies, NYCDOT will decide whether to reconstruct the bridge in kind, reconstruct the bridge at a reduced cost/size/capacity to reflect its current usage, or remove the bridge and develop a capital project to improve safety of the alternate routes.

Benefit cost percentile vs. safety benefits of 200 bridges compared to an alternate route.

Driven by data

In a city with as much legacy infrastructure as New York, it is important to continually reassess what is working well and what can be improved—especially given the outsized cost of reconstruction in a densely built environment. Moreover, the data gathered during this process showed who was using bridges and how they were being used. For example, the data showed that of 158 vehicular bridges, 22 of these bridges received over 75% of their benefits from pedestrians. This could justify redesigning these bridges upon reconstruction to benefit the true users of the bridge. The NYCDOT also was able to identify in the data small vehicular bridges which had truly outsized benefits despite their small size and low cost. This data could be used to justify expansion or creation of additional crossings.

The economic analysis screening tool quickly and inexpensively identified the best-performing and most cost-effective bridges. It also has drawn focus to those bridges whose costs may be questionable relative to their benefits. By focusing on those bridges with a low benefit-cost percentile, the NYCDOT can reassess how these bridges are being used, how much is being spent on their reconstruction and alternatives in their design—including removal. The NYCDOT also is using the safety benefits metric developed during this process to inform safety interventions on bridges and alternate routes. Despite these efforts at increasing efficiency and maximizing benefits per dollar spent, a multibillion-dollar unfunded need over 10 years is a large gap to close. Even if every bridge below the tenth percentile were to be miraculously rebuilt at no cost, that would only represent a small fraction of the gap that needs to be filled. Luckily, NYCDOT’s bridge capital budget is fully funded through the next five years, but by getting a head start in implementing economic analysis the agency hopes to be ready with facts and data-driven analysis to address the difficult decisions that will need to be made should funding fail to materialize.

About The Author: Hernandez is deputy director of economic analysis, Division of Finance, Contracts and Program Management, for NYCDOT.