A big pick in New Haven

In the principal transit corridor between New York and Boston, the interchange of I-95, I-91 and S.R. 34 in New Haven, Conn., is heavily travelled, to say the least.

I-95 N/S in particular traverses a densely developed urban area and borders environmentally sensitive New Haven Harbor. Built in the late 1950s, the interstate was designed to accommodate 40,000 vehicles per day. Today more than 140,000 vehicles travel the highway each day.

The Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT), the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the South Central Regional Council of Governments (COG), and other federal and local agencies jointly developed a strategy to address transit and transportation needs in the corridor. The 17-year, $2.2 billion New Haven Harbor Crossing (NHCC) Corridor Improvement Program was the result. It included the high-profile replacement of the I-95 crossing over New Haven Harbor, known locally as the “Q” Bridge, with a 10-lane extradosed version, the new Pearl Harbor Memorial Bridge.

One of the latter segments of the NHCC Corridor Improvement, a piece that tied other key components together, was the “Reconstruction of I-95/I-91/Rte. 34 Interchange: Contract E.” It took 51/2 years to build at a cost of $360 million. It was completed on time and on budget by the joint venture team of O&G Industries of Connecticut and Tutor Perini of California.

A crane is readied to remove the girder adjacent—by less than 3 ft—to the Cowles Building.

One bridge stood out

Contract E included the demolition of 20 bridges and the construction of 14 new ones. The take-down of one in particular, Bridge 3036, involved unique challenges that made its safe, successful demolition a highlight of the project.

Bridge 3036 was an elevated off-ramp from I-95S to Rte. 34W, located above Water Street in New Haven. It was a through-girder bridge, approximately 380 ft long and 50 ft wide. The superstructure consisted of two steel-plate, box-fascia beams measuring 9 ft 10 in. high with W33x152 floor beams spaced 8 ft on center. The floor beams were connected by two rows of diaphragms. Concrete decking and parapets were placed on the floor beams.

3036 was positioned oddly close to an historic factory: At its tightest juncture the bridge was less than 3 ft from the building. The Cowles Building was built in the late 1800s and is one of New Haven’s oldest and longest-used factories. Largely because of its historical significance the building was not taken by the state. The decision necessitated demolition in close quarters to the multi-story, wood and masonry (brick) building.

This extreme proximity was a concern. One nudge from a girder being raised off its piers would likely cause the 19th century masonry walls to collapse. Sparks from the torches cutting the girders could ignite the extremely dry, original wood window frames.

In a series of meetings spanning six months leading up to the demolition, representatives from CTDOT, contractor O&G/Tutor Perini, program coordinator WSP | Parsons Brinckerhoff, engineers Amman and Whitney/Louis Berger, H.W. Lochner and URS, along with utility United Illuminating, New Haven police and fire departments, and the Connecticut State Police put all aspects of the take-down plan together.

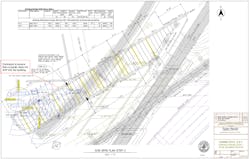

A schematic of the Bridge 3036 demolition plan.

The night of the big pick

The first significant step of the demolition was removing all of 3036’s concrete decking with a Cat 345 excavator fit with a “cruncher” to pulverize material. Excavated material was dropped to waiting loaders that took it from the site. The majority of the demolition occurred over Water Street and the highway. The integrity of the I-91S Exit 1 ramp onto Rte. 34 beneath had to be protected. This stage took one week to complete.

Deck removal was followed by plucking out the majority of the 46 floor beams connecting the large box-beam girders using a 60-ton Grove hydraulic crane with a 110-ft maximum boom length. Eleven 40-ft floor beams were left at either side of planned cuts to the beam fascia, and at ends to provide lateral stability to the through girders during cutting. Twenty-five percent was the minimum calculated to leave in place for the girder to stabilize itself without the removal of any fascia.

In anticipation of wind load, temporary lateral bracing was added. One-inch steel cabling was run back to the abutments where angle iron had been epoxied. Cable bracing also ran to 7,000-lb concrete blocks positioned on the ground.

Work on cutting and removing the through girders began on the southwest end of the bridge. On the ground on Water Street, a Manitowoc M-250 Series 2 crawler crane (with a heavy-lift top, 300-ton maximum pick and 330-ft maximum extension) was positioned on a 2-in.-thick steel deck plate under each track. A 10-in. plywood shim was put under one track to level the machine. This setup was installed and removed at Water Street each night.

A 35-ft spreader beam was employed, using 50-ft “chokers” running down to another beam with 2-in. steel vertical chokers. Knowing weights from original bridge drawings, crane operators knew how to tension the chains to approximately 95% of full load during the cutting process.

Bridge 3036 and the Cowles Building before girder removal.

Before any cuts could be made, the original lead paint had to be removed from the girders by needle gunning out to 2 ft on either side of the cut lines. Two smaller lengths of girder were the first to be extracted. Cut positions and sequences were based on the cantilever from the piers. Each cut took approximately 90 minutes to complete, with two men working simultaneously on opposite sides of the box, cutting first across the top flange, then down the web and finally across the bottom flange. Once both end cuts were completed and the girder segment was separated, the floor beams holding the piece to the girder on the opposite side of the bridge were cut and the segment lifted out. The crane then swung and lowered it onto a waiting flatbed. A twin segment on the parallel girder 40 ft away was taken next.

Falsework was erected underneath the segment being cut out before work proceeded. Temporary towers were installed, made from 400-kip shoring towers and grillage beams that were cribbed into position. Extractions were done with a minimum of falsework in order to clear the I-91 ramp and Water Street below. Because 3036 spanned the I-91S exit ramp, there was not enough clearance available to remove the through girders with a single crane. This is one reason why a pair of cranes was required to remove the largest 118-ft-long, 220,000-lb segment.

Because protecting the Cowles Building was imperative, a second pair of cuts was made that would take the 118-ft segment next and leave as small a segment as practicable next to the structure. That made for less weight to handle and distanced cutting as far away from the building as possible.

The decision to set the size of the large piece also was a practical economic matter driven by Tutor Perini, which wanted to salvage it for use in roadwork at the ongoing Hudson Yards development on Manhattan’s west side.

The big tandem pick enlisted the Manitowoc M-250 crawler and a 275-ton Grove GMK5275 hydraulic crane rented from an owner/operator. In the interest of time, renting this second crane was chosen over disassembling, moving and reassembling the Manitowoc on the opposite side of the bridge where it could have performed the lift by itself. In its current position, it could not safely extend and raise the large segment alone.

Bridge 3036 and the Cowles Building after girder removal.

The hydraulic crane hooked onto the northeasterly end of the beam first. Next the M250 hooked onto the opposite end. Together they applied tension to 95% of segment weight and the bisections were made. With crane mats set onto the lower bridge deck next to 3036, both machines hoisted the piece, swung it and lowered it onto dunnage. Now in a position to be safely hoisted, the Manitowoc (with a 70-ft spreader beam and 2.5-in. chokers) picked it back up and walked it down Water Street and set it on a trailer. Moving this lengthy and heavy piece gave the crew its greatest cause for concern of the night. Four rope lines kept it stable. All work proceeded to plan. Even the Manitowoc, known to gel when temperatures dipped to 20°F, ran flawlessly.

Temperatures on the nights of girder cutting and extraction fell to single digits; wind chill pushed the temperature below zero. Stoppages for snow or high wind (over 20 mph) did occur. Crews worked safely without any incidents, and even felt invigorated by the challenges of the environment and tasks at hand. Structures Superintendent Bob Nardi, who, along with Steel Superintendent Paul Parlapiano and Night Superintendent Peter Hinman, directed the work, said, “Everything came together those nights. It went like clockwork. And I got those guys lots of coffee.”

“As is usually the case with a big pick like 3036, we met in the field the night before it was undertaken,” said Charles Johnson, P.E., vice president and Contract E resident engineer for Louis Berger, inspector on the project. “The CTDOT project engineer, job superintendent, ironworker superintendent and my structural inspectors made sure we were not overlooking something and that everything was prepared. With the alternate two-crane setup to pick from the opposite side and using an elaborate bracing system, the O&G/Tutor Perini team went forward and accomplished the work without a hitch. Given the mass of the girder, the extreme cold and the tight proximity to an historic building, [it was] quite an accomplishment.”