Girder connection provides bridge win in mountainous Colorado region

Glenwood Springs, Colorado is recognized as one of the best small towns in the U.S., as well as one of the most walkable; it was even declared the most fun town in America by USA Today.

Its hot springs, ski resorts, and outdoor amenities make the town a popular vacation destination, and its location just off I-70 makes it an easy mountain town to get to.

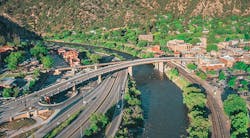

But that ease of entrance was being strangled by an aging and functionally obsolete, nine-span, 676-ft-long steel plate girder bridge constructed in the early 1950s. The bridge, which carries State Highway 82 over I-70, the Colorado River, and the Union Pacific Railroad before descending into the historic downtown business district of Glenwood Springs, had four narrow lanes that bottlenecked traffic flow.

Enter the new Grand Avenue Bridge, a Colorado DOT (CDOT) project that reinvented the entrance to downtown—and even created dynamic use for visitors below.

Designed by RS&H, the new structure is a combination of two independent but connected structural units: a curved, five-span continuous steel trapezoidal tub girder bridge, and a three-span cast-in-place concrete bridge. Nearly 300 ft longer than the bridge it replaces, the Grand Avenue Bridge represents both state-of-the-art steel tub girder design and the architectural ingenuity possible with cast-in-place concrete.

The Grand Avenue Bridge is notable not only for its community-tailored design, but also for the traffic-conscious method used to build it.

A simple-made-continuous girder connection allowed the first three spans of the five-span steel tub unit to be fully constructed while the existing bridge was still in use. While simple-made-continuous connections are common in pretensioned girder construction, this project marked an innovative use of this technology within a steel tub girder bridge.

RS&H provided project management, bridge, and structural design, roadway alternatives, hydrology, traffic management, and post-design services for the bridge replacement. A joint venture of Granite/RLW served as the general contractor on the project.

Working Together to Find a Better Way

While RS&H Bridge Group Leader Clint Krajnik, P.E., S.E., and his team worked to realize the bridge’s future, they not only had to keep in mind the proposed technical requirements, but they also had to consider the structure’s history.

The original Grand Avenue Bridge opened in 1953 as a two-lane road. When traffic across the bridge increased, it widened to a four-lane road. Builders created the extra space by swallowing what had been a pedestrian sidewalk into the bridge lanes. Even with the addition, the four lanes were each a little over 9 ft wide.

Despite years of traffic issues, previous attempts by CDOT to replace the bridge failed. The city’s 10,000 residents had historically opposed replacement attempts due to beliefs that a new bridge should be relocated out of the city’s downtown or that the existing structure should be preserved.

With that history in mind, the state mitigated the potential for public pushback by utilizing a construction manager/general contractor (CM/GC) delivery method, which brings in the contractor to work for the state during the design phase. This allows the public to form a relationship with the contractor before actual construction begins and allows constructability feedback during the design process.

The project team dedicated a lot of time to hearing residents’ feedback and ensuring that they understood the project and were involved in decisions surrounding it. The team developed and screened 12 major alternatives, which resulted in a project that ultimately gained strong stakeholder support.

“To support the project, the community and elected officials were adamant that the new bridges had to have a timeless aesthetic that fit the historic context of the project location, which was also required mitigation,” said CDOT Central Program Engineer Roland Wagner, P.E.

The project team worked closely with the Glenwood Springs Downtown Development Authority on appropriate aesthetic treatments similar to adjacent historic buildings at the historic districts on both sides of the bridges. The weathering steel tub girders were selected because they blended in with a historic context, as compared to other girders systems such as concrete tub girders, which would have more of an urban aesthetic.

High Pain, Low Duration

Based on public feedback, the team decided to shut down the whole bridge for a short period of time, instead of closing parts of the bridge for a much longer duration. Under a traditional phased construction, the road would have been partly shut down for around a year, with construction necessitating three months of single-lane closures and nine months of two-lane closures on the four-lane bridge.

Instead, with this alternative strategy, the bridge had a planned shutdown of 95 days, saving CDOT more than an estimated $2 million in the process.

“It seemed like unanimously we heard residents elect the ‘high pain, low duration’ construction plan, with the caveat that the ‘pain’ needed to be in an off-season,” Wagner said. “The local Glenwood Springs resort community is very dependent on the economic activity that occurs between Memorial Day and Labor Day.”

The Right Aesthetic & Approach

RS&H’s final design on the curved alignment more directly connects State Highway 82 to I-70 and improves traffic operations and the local street and pedestrian network.

The previous four-lane state highway was routed through two 90° turns, with numerous business accesses including head-in parking and discontinuous sidewalks.

The new bridge alignment flies over the parking lot for the Hot Springs Pool, moving the roadway away from the pool area and more smoothly tying the I-70 interchange to the bridge. This new alignment helped to gain support for the project from two major stakeholders, the Hot Springs Pool and the city of Glenwood Springs.

The new route turned the former state highway into a low-speed city street in the tourist-oriented area on the west side of the pool. The design incorporated unique signal phasing, roundabouts, and modern pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure.

The bridge’s downtown section was a major consideration from the project’s very beginning. While the north section of the bridge spans I-70, the Colorado River, and the Union Pacific Railroad, the south section stretches between historic Glenwood Springs buildings, which concerned residents.

To account for the unique design constraints and alleviate any resident worries, architects and engineers created two separate structures, which eventually were connected.

The section spanning over the river and highway is comprised of 6-ft deep steel tub girders that can accommodate long spans, which kept the team from having to place piers in the middle of the Colorado River or the I-70 highway median. The second section, hovering over the city’s downtown, consists of a thinner, three-span, cast-in-place concrete slab. This minimized the bridge’s presence in the downtown skyline and opened the area underneath the bridge for a planned community gathering place.

The downtown slab section features arched overhangs that taper from 3 ft of thickness to 9 in. over about 10 ft. This taper increases the natural light reaching the below pedestrian plaza area.

The team added visual interest to the slab’s underside—part of which also functions as the community plaza’s roof—by breaking up the otherwise smooth expanse with 9-in. deep impressions cast into the concrete. The back of the concrete traffic barrier uses similar rectangular impressions, paying homage to the city’s historical aesthetic.

At the transition between the two sections just north of downtown, the ends of the 6-ft deep steel tub girders are notched, which allows for an elegant transition between the two structures and avoids the awkward aesthetics of a stepped pier cap.

Bridging Two Structures Together

At the third interior pier of the steel tub girder unit, a simple-made-continuous girder connection was used to allow the northern three spans of the bridge to be fully constructed including the deck, with the remaining two spans of girders and deck constructed later.

“The last two spans were ultimately connected to the first three via a concrete diaphragm between girder ends combined with negative moment reinforcing in the deck,” RS&H’s Krajnik said.

Girder-end bearing plates were added to the bottom portion of tub ends to spread out the girder compressive forces in the bottom flange and lower portion of webs into the concrete diaphragm. Stay-in-place steel side forms between the ends of webs and bottom flanges were used at this connection.

“We added bolt heads to the outside of the web forms to mimic the look of the other typical steel web splices along the bridge,” Krajnik said. “Even other bridge engineers will have a tough time telling there is a concrete girder closure here.”

At the transition between the steel tub bridge and an adjoining concrete slab bridge (Unit 2), the steel tub girder ends were notched to allow them to directly support the end of the thinner concrete slab bridge.

Movement articulation at the transition was accomplished with two levels of sliding bearings: between the tub girders and pier columns, and between the slab bridge and each girder notch. The lower part of the tub girder notches was filled with concrete to allow use of standard bearing details for the upper bearing devices.

At the two most severely skewed pier supports at the north end of the bridge, multiple lines of perpendicularly oriented diaphragms were used to create a stiffened zone, in lieu of using a single pier diaphragm oriented along the skew.

“This approach required additional material, but it made fabrication and erection easier,” Krajnik said. “We were able to minimize differential deflections between tub girder web lines, as well as girder torsions due to the skew and curvature.”

Award-Winning Effort

Construction on the new Grand Avenue Bridge was completed in 2018. When the bridge opened, around 3,000 locals attended the ribbon cutting. (Keep in mind, the city only has about 10,000 residents.)

“As incredible as the ribbon cutting and bridge walk and team celebrations were, I was still perplexed as to why so many people showed up after they had been severely impacted with hour-long delays in their daily traveling routines for three months,” Wagner said. “In reflection, I believe the support we received at the ribbon cutting at the tail end of the project was due to the systematic development of informed consent process that the project team started at the beginning of the project.

“If you bring your stakeholders along with you, even if they don’t always support the project and decisions along the way, in the end they will likely support the end result.”

In February this year, the American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC) gave the Grand Avenue Bridge the National Prize Bridge Award for the Medium Span category. The bridge was lauded for its “creativity of the designers and the skills of the constructors who collaborated to make them reality,” according to AISC President Charles J. Carter.

The project also has special meaning for Wagner, who grew up in Glenwood Springs.

“I can attest that the community is very proud of the project,” Wagner said. “The team’s enduring success will be the bridges that are admired alongside the public spaces that the project created, which will be enjoyed for decades to come.”