By: Grace Stansbery

Even in the strongest economy, America has been challenged with failing infrastructure. Now, thanks in no small part to COVID-19, times are especially difficult. As we enter a true recession, the current pandemic has greatly affected the economy, with demand and supply-side disruptions, a sharp drop in employment, and stay-at-home orders seriously impacting sales taxes, revenues from transportation and gas tax, and increased demand on all levels of government. Many state and local agencies are now expecting revenue shortfalls, or, at the very least, battling uncertainty and hesitation. As we respond to these challenges and plan a path forward, it can be helpful to look back at similar situations and the tools used in the past.

Learning from Roseville, California during the 2008 Recession

Roseville is the largest city in Placer County, just northeast of Sacramento, with over 1,000 lane miles, the majority of which are residential roads. In 2008, when the Great Recession hit, many aspects of the economy screeched to a halt, including infrastructure projects, municipal funding, and community revenues from tax and toll initiatives. The city of Roseville was no different, contending with budget cuts, loss of staff members, and a hiring freeze.

Jerry Dankbar, the city’s roads superintendent, has been a steward of Roseville’s network since 2000. Dankbar’s team was stretched thin. They were expected to maintain the same success the city’s preservation plan had delivered for the past few years, during great uncertainty in the economy.

However, despite the massive challenges they faced, Dankbar and his team leveraged learnings and experience from their existing preservation program to continue maintaining a successful road network, even as other cities and counties struggled to keep their networks in less-than average condition.

Immediately following the recession, Roseville was able to address more than one-third of all arterials in its network, nearly eliminate taxpayer complaints related to road construction, and maintain the still-growing network, keeping it in good condition, as evidenced in the following graph, which illustrates pavement quality across centerlane miles over a period of 10 years.

What does it take to maintain a road network in a recession?

Dankbar and his team credit their success to three things, each a part of their preservation and in-place recycling programs: Shovel-ready projects, which allowed them to make the best use of federal funding; a toolbox full of proven treatments, techniques, and strategies for cost-effective approaches to each project; and proactive communication across a wide-spanning network of decision-makers and end-users.

“Because of the preservation program, our roads were in good shape when the economy tanked,” said Dankbar. “That meant our backlog was more manageable, and it was easier to get our arms around how to move forward.”

“That [knowledge of preservation and recycling] is the same thing that will benefit us as we look ahead to next year, when we start to see the impact from COVID-19 and the 2020 economy,” says Dankbar.

Roseville’s Preservation & In-place Recycling Program

When Roseville began its preservation program in 2000, Dankbar was focused on making better use of taxpayer dollars and finding new ways to solve old problems.

“At that time, even state organizations didn’t have much available,” said Dankbar. “A lot of the insights we learned were from observing others and trying new treatments on our own network.”

Dankbar and his team traveled across the country to conduct site visits, learn from others, exchange information, and bring new treatments home to Roseville to test and learn: “Fortunately, there’s so much more available to road managers now. Back then, we had to learn it through trial and error and the experience of local contractors.”

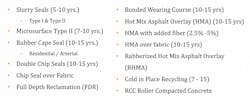

Today, thanks to Dankbar’s team, the city of Roseville uses a wide range of treatments.

2009

After Dankbar’s team began the Roseville Preservation Program, nearly nine years of learning had passed before it would be put to its greatest test: Reduced revenues from the 2008 economy.

“As the recession hit, we had to make a 15-25% cut in our budget,” Dankbar said. “The whole city was feeling it at the time.”

By 2009, in response to the recession, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was released to support city infrastructure. The stimulus would allow communities to continue pushing forward with existing plans. However, it was stipulated that the funding could only be applied toward arterial roadways. and the projects needed to be completed quickly, which meant agencies would have to act faster than ever.

For Roseville, securing this funding would mean they could actually “gain ground” for the network during the recession.

Dankbar and his team had already built a plan for Roseville’s network through its preservation program, which anticipated and scheduled new projects and made use of past project successes. This meant the city knew which roads needed treatment, which treatments were most successful in the area, and which projects would have maximum impact on the overall network health. Essentially, they had done the work upfront. The engineering staff were then able to put together the projects and get them out to bid , thus securing the available funding.

In addition to applying city funds to the fullest extent, Roseville was able to borrow ARRA funding from neighboring cities and counties that did not have a series of projects prepared. (Repayment would take place over the next few years with local gas tax funding.) This allowed a massive amount of work to be completed in 2009 and 2010, giving Roseville a big jump on its network health.

In the end, Roseville addressed one-third of its arterial roads. In addition to federal funding, Dankbar attributes this success to multiple factors, including lower labor and material costs: “Although the years following 2008 were a difficult time for everyone, we had a few things working in our favor. Not only were we able to utilize federal funds, but project costs were lower than expected as a result of the economy, as well.” Dankbar says this was a win-win for contractors who were eager to have the work and able to secure materials at lower prices.

While it was federal funding that allowed Roseville to pull off some big wins in 2009, as agencies now look toward 2021, one of the greatest items on any agency’s to-do list could be much less tangible—communication.

Vehemently sticking to the plan

“Maintaining a network isn’t as simple as understanding the needs of your network and applying the tools—it takes buy in,” said Dankbar.

Even the most well-meaning agencies can get stymied when elected officials or residents don’t understand where or why tax dollars are being spent, especially with a preservation program.

“We do a lot of communicating—more than I ever thought any superintendent would,” Dankbar joked. “But that keeps people engaged, and it keeps the program working.”

Dankbar and his team use tailored programs to educate on network impact. For decision-makers and elected officials, there is one-on-one communication and updated presentations at city council meetings. For residents, the goal is to build an understanding so that future projects aren’t sidelined in favor of “the squeaky wheel” roads. Roseville notifies residents in neighborhood forums, in-person conversations, and direct mail initiatives to not only alert residents that work is planned for their area, but help them understand what the treatment is and the expected result of the project. “Residents really grow to appreciate roadwork when they understand why it’s happening and how we [the city] are using their tax dollars more efficiently,” Dankbar said.

With more and more factors changing in the COVID-19 atmosphere, and budgets coming under scrutiny, cities and counties will need to be in touch with their residents and decision-makers more frequently than ever. Roseville’s success during the last major recession is a great example for agencies to follow in the most challenging of times. In the current atmosphere, cities and counties will have to learn how to adapt to changing decisions and leverage new tools to maintain their planning if they want to keep building toward healthier road networks.