Concrete pavement preservation makes Oklahoma’s turnpikes smooth, safe, and affordable without reconstruction

By: Kristin Dispenza

Oklahoma’s interstate construction history provides an inherent experiment allowing the comparison of asphalt versus concrete highway surface performance. It also allows for comparison between complete reconstruction and concrete pavement preservation (CPP) repair techniques.

The result? Dollar-for-dollar, Oklahoma can repair seven times the number of concrete pavement lane-miles using CPP as opposed to performing complete reconstruction.

Oklahoma’s History of Asphalt and Concrete Highway Construction

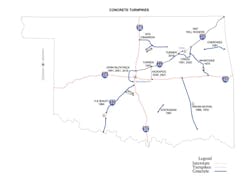

Prior to 1950, Oklahoma had no interstates and no four-lane divided highways. But demand for these highways was strong, so the Oklahoma Turnpike Authority (OTA) was created to build the Turner Turnpike, which connects Oklahoma City and Tulsa, as well as to open future alignments. By 1953, the 88-mile-long Turner Turnpike was opened and future alignments were then authorized in 1954.

The Turner Turnpike, as well as the 100-mile-long Will Rogers Turnpike, which opened in 1957, were both asphalt roadways. In 1964, the OTA began constructing highways with concrete surfaces. The first one, opened in 1965, was the 86-mile-long Bailey Turnpike. Then came the 53-mile-long Muskogee Turnpike, opened in 1969; the 110-mile-long Indian Nation Turnpike, opened in 1970; and the 66-mile-long Cimarron Turnpike, opened in 1975. All four of these highways are four-lane divided highways constructed of plain jointed concrete pavement.

With a network of turnpikes serving the state (as well as the east-west I-40, north-south I-35, and northeast-southwest I-44), the OTA’s focus shifted to maintenance instead of new construction. Between 1990 and 2018, according to Joe Echelle, assistant executive director of OTA, the concrete highways needed only isolated panel replacement where subgrade failures had occurred, along with some short reconstruction projects. By comparison, more than 130 repair projects were conducted on each of the two asphalt roadways in OTA’s jurisdiction (the Turner Turnpike and Will Rogers Turnpike) during the same time frame.

“During our summer seasons, when the state experiences higher traffic volumes, we’ve been faced with repair procedures such as mill and inlay for our asphalt highways,” said Echelle. “But the concrete turnpikes have had almost no major projects—only 30 to 50 projects in the last 50 years, compared to the 260 or so for asphalt. To be able to get a 50- to 60-year service life out of concrete pavement is a major advantage.”

Saving Money with Concrete Pavement Preservation

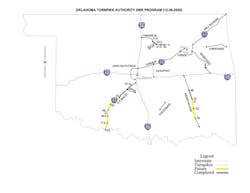

In 2020, Oklahoma’s concrete pavements were due to begin a maintenance cycle. By the end of that year, CPP (consisting of selected panel replacements, dowel bar retrofit [DBR], and diamond grinding) had been completed on portions of the Cimarron, Bailey, and Indian Nation Turnpikes.

DBR restores load transfer across transverse joints and cracks by installing dowel bars to link adjoining slabs. The bars prevent differential vertical movement of the slabs at the joints and cracks, eliminating the formation of faults or step-offs. Diamond grinding—in which a thin layer of hardened concrete surface is removed using a self-propelled machine outfitted with diamond saw blades—improves smoothness on the finished pavement. Grinding also increases pavement macro-texture, improving drainage and mitigating the chance of hydroplaning in wet weather, and achieves a longitudinal texture that reduces pavement noise. Together, CPP techniques can return a concrete roadway to a structurally sound, smooth condition, sometimes even exceeding the smoothness and noise values attained at the time of construction.

Echelle notes that in Oklahoma, where local DBR and diamond grinding crews are not available and out-of-state contractors must be brought in, the state maximizes its budget by grouping projects together to get the most value.

The Cimarron Turnpike had several severely cracked panels. Where cracks occupied the middle portion of the panel, OTA performed stitching. Stitching operations use tie bars to maintain aggregate interlock, providing added reinforcement and strength to longitudinal cracks and unreinforced longitudinal joints. The tie bars inhibit vertical and horizontal movement at the crack or joint. Where there were larger cracks or faulting on the Cimarron Turnpike, the OTA chose panel replacement, with OTA maintenance crews performing the repairs. Because the panels requiring replacement were few in number and, for the most part, not contiguous, crews could not achieve a smooth transition between panels with screeding alone and relied on diamond grinding to achieve smoothness on the finished pavement. Panel dimensions were approximately 15 ft long by 12 ft wide. Despite the colder climate and greater weather-related delays experienced in northern Oklahoma compared to the southern part of the state, all scheduled CPP work on the Cimarron Turnpike was completed by the end of 2020. The cost was $14 million for 19 miles of selected panel replacements, DBR on all panels, and diamond grinding of an area covering approximately 500,000 sq yd.

Like the Cimarron Turnpike, the Bailey Turnpike required panel replacements on selected cracked panels, DBR on all new panels, and 500,000 sq yd of diamond grinding. The project cost was $13.7 million for an 18-mile repair area. The Indian Nation Turnpike, which was one of the roughest pavements at the outset of the project, received similar repairs. Cost for panel replacement, DBR, and diamond grinding of 500,000 sq yd on the Indian Nation Turnpike was $12 million for an 18-mile repair area.

All three of the CPP projects, with their diamond-ground finished surfaces, received positive reviews from the driving public.

“Anyone who works highway construction knows that for every ‘attaboy’ you get, there are many more complaints. But for the first time in my career, we’ve had quite a few people reaching out via social media, and through other channels, thanking us for how much smoother the pavement has been on our turnpikes. The compliments started coming in as soon as we completed the diamond grinding,” said Echelle.

CPP in Oklahoma Costs Only 15% of the Cost of Reconstruction

Oklahoma faces challenges in stretching its budget to cover necessary highway repairs. The OTA is tasked with accommodating Oklahomans’ demands for highway speed limits of up to 80 mph by providing smooth, safe, drivable roads. However, the state’s turnpikes, which already have speed limits of 75 to 80 mph, have experienced pavement damage that is directly attributable to those limits.

“The bounce effect from faulted joints gets significantly worse when vehicles are traveling at high speeds,” explained Echelle. “And these roadways saw 6,000 to 25,000 vehicles per day, with roughly 10% being trucks.”

Costs of reconstruction add up. Including shoulder work and drainage, the cost to reconstruct a pavement is approximately $4 million per mile of four-lane highway. OTA’s approach, when performing reconstruction, has been to limit work to 3 to 4 miles at a time. This means work on an individual section of road takes several years, considering interruptions due to winter weather. CPP, however, costs less than $600,000 per mile of four-lane highway (based on Oklahoma’s 2020 contract prices), and construction can take place in a single season.

“Depending on the number of panel replacements necessary, our 2020 projects took five to seven months to complete. Once the crews were on site, saw cutting, bar installation, and diamond grinding went very quickly. This was true despite the fact that the OTA did not allow the contractor to install dowel bars in both lanes unless they diamond ground one of those lanes. This prevented drivers on a single reopened lane from having to drive on a surface that had its dowel bars installed but had not been diamond ground for smoothness,” said Echelle.

And with the cost of CPP being only 15% that of reconstruction, Oklahoma can repair seven times the length of roadway for every dollar spent.

“We achieve such savings because consultants can quickly and cost-effectively design dowel bar retrofit and diamond grinding work,” said Echelle. “These CPP techniques are also cost-effective to administer, because construction managers don’t have to perform testing; their responsibilities are limited to jobsite oversight.”

“Considering the expense, full reconstruction would take us 20 to 30 years—and our roads are already rough. We want to get the necessary work done in four to five years,” continued Echelle.

With 163 total centerline miles to repair between 2020 and 2025—including the work already done on the Cimarron, Bailey, and Indian Nation turnpikes in 2020—OTA estimates a total cost of only $95 million. It would take a projected $634 million to perform reconstruction.

Fortunately, CPP methods—especially panel replacement, DBR, and diamond grinding—are well-suited to Oklahoma’s 45- to 55-year-old pavements. The preserved concrete highways are expected to provide at least 15 to 20 more years of service, with minimal maintenance.

“With increasing demands and diminishing transportation funding, roadway owners are compelled to look for new and innovative ways to stretch their budgets and maximize pavement longevity,” said John Roberts, executive director, International Grooving & Grinding Association. “It is truly good fortune that Oklahoma chose to build many of their roadways using long-lasting, sustainable concrete pavement. It is even more fortunate for the taxpayers of Oklahoma that their transportation officials were willing to look at best practices abroad and develop a system of pavement renewal that is economical, long-lasting, and safe. These challenging times require innovative thinking and the courage to follow through. Oklahoma serves as the model for concrete pavement preservation at its finest.”

About The Author: Dispenza is with Advancing Organizational Excellence (AOE).