By: Brian W. Budzynski

Virtual reality (VR) has been a staple of mass media for decades, but only in the abstract.

Popularized in television shows and in the movies, largely science fiction-related, VR has now moved past static media to the realm of interactive video games, and, to some degree, infrastructure project planning and implementation. Among the aspects of project planning and design where VR is presently and is expected in the future to find use are client presentations, public outreach, training, physical construction, and site and facility maintenance. It’s a large nut to crack, and there is still much ground to cover before a project manager can step out onto a stripped-down parcel of land, don a headset, and take virtual control of the myriad aspects of a project site. But the first steps have already begun, and agencies both in the U.S. and elsewhere around the world are striding headlong into what they see as the future of construction planning.

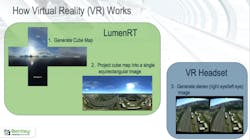

The generation of live cubes can allow an agency to share VR design concepts.

More than the headset

“When people think of VR, it’s like three blind men and an elephant,” David Huie, marketing manager for Bentley Systems’ LumenRT, told Roads & Bridges. “Each one is squeezing a different part of the elephant and they’re not quite sure what it is. When planners talk about VR, we talk about the macro level—everything from immersive experiences all the way out to high-end augmented reality, where you’re putting on glasses, and the program is overlaying VR onto actual reality. But VR is more than just putting on a headset. It is an interactive, immersive visualization tool that can be used to construct highly interactive scenes for presentations, public outreach, planning and design.”

The bridge from augmented reality to virtual reality is a hazy one, often misunderstood, but according to Huie the distinction is less related to the technology than to its purpose in application.

“The big difference between traditional visualization technology and the new world of immersive VR technology,” Huie said, “is we now have the ability to engage with the client or customer. With immersive VR you can get answers to questions like what’s this going to look like at night, how will it effect traffic—and get them instantly. And that’s the real breakthrough.”

Interfaces such as LumenRT allow a person to position themselves anywhere in a projected area, to assume any point of view they desire, and achieve a full environmental context within the project site. In fact, you could “fly” through the site, if you desired. But the purpose is less the generation of excitement than the near-tangible presentation of finality.

“DOTs struggle with the types of questions they are going to be asked [when a project begins],” David Burdick, senior product manager for Bentley, told Roads & Bridges. “Things come out of left field, especially at public review meetings.” Such challenges are presently being aided by the integration of VR into public presentations and preliminary design schema.

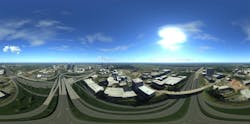

In layman’s terms how it works is a live cube is generated, which consists of a cube map of a site which is made into a single equirectangular image. Within the cube, using LumenRT, an engineer can add more or less anything they like: roads, buildings, pedestrians, foliage, electrical polls and wiring, businesses, playgrounds and so forth, and then imbue the site, through a VR headset, to allow for any perspective the viewer might wish to have—such as turning a full 360°, walking down a street or seeing a site from multiple elevations. The idea is to get all stakeholders on the same level of understanding, regardless of their level of expertise, by putting the data into a format anyone can readily understand. The result is that everyone gets on the same page quickly.

An example of an equirectangular view that was created for the Georgia DOT.

On the VERG

In the Washington State Department of Transportation’s Visual Engineering Resource Group (VERG), virtual reality is within arm’s reach, though not quite at hand. Yet recent work done within the group has demonstrated the viability of moving beyond 3-D visuals and into the world of full VR.

“The problems that we face are 19th and 20th century driven, but we can’t use 20th-century toolsets to get us out of those problems,” VERG Manager Kurt Stiles told Roads & Bridges. “We’ve got to have 21st-century tools. We’ve got to break down the silos and barriers.”

Over the past few years, Stiles and colleague Ron Jones, who is the visualization engineer for VERG, have applied immersive modeling to several projects in the state, as a means of both demonstrating the technology’s value to the DOT and educating public stakeholders as to the possibilities offered by its use.

“People have perceptions that using 3-D modeling for visualization is a costly and time-consuming and complicated process that only experts can produce,” Stiles said, “but that’s not the case at all. If you’re doing any kind of engineering design, you can be your own visualization specialist.”

Most recently, VERG created a fully interactive model for the city of Zillah, located on Rte. 82 south of Yakima, which was exploring the possibility of constructing a new parkway to connect a business district with several residential developments. The resulting visualization enabled city officials and residents alike to “see” what their community would look like with this new corridor running through it.

“You can take your infrastructure and look far into the future, animate it and tell really any story you want with it to any type of stakeholder,” Stiles said. “On the Zillah Parkway, we were trying to educate people to take a risk, to visualize early and often. You don’t need a Ph.D. in civil engineering to make this happen.”

For the Zillah visualization, Jones created a live cube that was then shared with city officials and stakeholders: “The cube was a self-contained product which was sent to anyone with a computer, basically. It offered a scene they could navigate through, zoom in and out of, and run an animation within (i.e., a preset tour through the corridor project).”

At present much of VERG’s work with 3-D modeling and VR has been to the purpose of outreach and public/agency interest—to aid the fruition of projects—but Stiles sees more widespread application perhaps at the ready, and the scope is surprisingly (and importantly) much smaller than the project level.

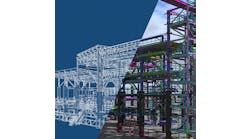

“Where this technology really helps is not necessarily the big-ticket project level, though it does, of course,” he said, “but rather with the little problems: curb return issues, sight distance issues or access- or safety-driven issues. For example, on a bridge you don’t have to look at the whole bridge, you can focus on what the contractor is having a particular issue with, such as the wing wall or the abutment or the stiffening truss, and help them do their job. This works equally well from a design and maintenance point of view.”

VR and 3-D immersive modeling can allow a viewer/user to explore any aspect of a virtual environment, from any perspective.

Everyone will be specialized

Other DOTs are slipping into the VR stream. Recently, the Alabama Department of Transportation, having reservations about public reaction to its plans for a new bridge spanning the Mobile River at a point where it is a federal navigation channel, solicited the creation of a simulation of the city of Mobile. The resulting model not only allowed people to see how the bridge would come together, but it also allowed them to interactively participate, to place themselves at their respective place of business or home within the model scene, in order to visualize how the final project would impact their lives and community.

The Nevada DOT has begun experimenting with flying drones over its projects on a daily basis and using ContextCapture to produce dailies to monitor progress at their home office. Ohio, Pennsylvania and Connecticut also are presently engaged with VR applications.

But the technology has some ground yet to gain in order to be of utmost value to groups like VERG.

“We need to make it work for transportation planning, moving cars, going multimodal,” Stiles said. “That would include traffic patterning, smart vehicle movements, intersection signal control. This would need to be integrated into more data analysis software, to be able to take the model and see the stresses in a space-frame (e.g., a bridge); to really have them represented through the visualization would be pretty powerful. These types of things are important to transportation engineering. Eventually, groups like VERG will go away, and the skill set will transfer to the designers and engineers themselves; everyone will have it, you won’t need a specialized group. Everyone will be specialized.”

Such reservations notwithstanding, progress appears to be otherwise unimpeded.

“The construction industry is pushing for 3-D and VR,” Stiles conceded. “In their world, time is absolute money. Anything that can ramp up understanding and accuracy of their equipment and process planning is really going to be adopted quickly.”

“2017 is really the year of VR experimentation for most infrastructure companies,” Huie said. “AECOM, HNTB, CH2M and more are all experimenting with VR, generating media, more or less laying the groundwork for 2018, which we think will be the year of VR implementation. As VR becomes more mature and sophisticated, along with augmented reality, then you’ll see it used in the engineering and operations sides of projects. The architectural segment is a bit ahead of the infrastructural side. They tend to have larger graphics shops, so they’re well-versed. But [in terms of] applying VR in an engineering context, construction infrastructure might well take the lead.

“Basically,” Huie concluded, “if a picture’s worth a thousand words, a live cube is worth a million.”

VERG created a virtual corridor for a proposed project in Zillah, Wash.

About The Author: Budzynski is managing editor of Roads & Bridges.