Smarter salt spreading results in lower costs and improved safety

It is often said that it’s hard to put a price tag on safety. But when it comes to winter road safety, there are numerous sources that have tried to do just that with some particularly eye-opening results.

A report from the environmental engineering department at Washington State University, for example, estimated in 2015 that the U.S. spends $2.3 billion each year to remove snow and ice from highways. This figure did not include the added costs associated with salting city, county, and rural roads.

Another survey by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) in that same year documented escalating costs to keep our roads safe. Of the 23 states that participated in the survey, Pennsylvania reported the highest expenses, spending $272 million that year. The state’s transportation department additionally estimated a total of 2.5 million man-hours needed to respond to the storms. Even states as far south as Louisiana and Mississippi reported seven-figure winter cleanup bills. In 2015, Louisiana spent $1.2 million and Mississippi $3.1 million.

These numbers are not constants. Depending on weather conditions, they can fluctuate dramatically from one year to the next. Adding to the cost uncertainty is the unstable cost of salt, which has been rising dramatically in recent years due to supply shortages.

Although salt is an abundant global resource, shortages occur when there is not enough salt harvested above ground. The widely publicized salt shortage of 2018 is still having a profound effect on budgets. As the intensity and duration of winter storms have been increasing, salt shortages have existed to some degree since the brutal winter of 2013 depleted stockpiles.

The 2018 shortage, however, is more severe because late spring snowstorms forced municipalities to deplete their inventories early in the year. New York, for example, already reported in spring that it had used more salt this past winter, spreading more than 460,000 tons before the season had officially ended. The Massachusetts DOT similarly reported in June 2018 that it had exceeded the state’s $42 million snow removal budget, spending upwards of $70 million for labor, overtime, and salt supplies.

The shortage became more critical midyear as the result of a lengthy labor dispute that shut down an Ontario salt mine—one of the largest salt mines in the world—for nearly three months. Magnifying the problem was a water leak at an Ohio-based mine that reduced the amount of salt harvested.

As the result of projected shortages, some municipalities have seen salt bids as much as three times higher than the previous year. The Ohio Township Association, for example, reported the average 2017 price paid at $48 per ton. The 2018 bids, in contrast, ranged between $80 and $110 per ton.

These numbers only reflect the cost to put the salt down. Multiple sources have documented the additional costs of cleanup and road repairs necessitated by the corrosive effects of too much road salt. That same study from Washington State University estimated the U.S. spends an additional $5 billion to pay for the resulting damage caused by salt. A study in Utah estimated that salt corrosion costs $16 to $19 billion per year nationwide.

An article that appeared in Roads & Bridges in September 2018 estimated the cost to taxpayers at a minimum of $1,800 per ton of salt spread to repair the damage caused by winter salting. Multiply that by the estimated 15-22 million tons of salt that is applied each year in the U.S. to appreciate the full cost.

WHY IS SALT SO COSTLY TO CLEAN UP OR REMOVE?

The corrosive effects of road salt are well documented. According to des.nh.gov, chloride can penetrate and deteriorate concrete on bridge decking and parking garage structures, and damage reinforcing rods, compromising structural integrity. It also damages vehicle parts such as brake linings, frames, and bumpers, and corrodes the body’s metal. It impacts railroad crossing warning equipment and power line utilities by conducting electrical current leaks across the insulator that may lead to loss of current, shorting of transmission lines, and damage to wooden pole frames.

According to the city of Madison, Wisconsin, which issued a report of the Salt Use Subcommittee to the Commission on the Environment, the cost of corrosion damage and corrosion protection practices for highways and the automobile industry combined have been reported to cost upwards of $19 billion annually.

And that does not even begin to consider the cost to the environment. When salt runs off roads and finds its way into streams and rivers, it can cause irrevocable damage to water quality and harm aquatic life. Excess salt that makes its way into the soil on the sides of the road can also cause plants to die, necessitating the need for and cost of replanting grass and trees and restoring soil pH levels.

THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF SALTING LESS

An obvious solution to rising costs is to use less salt. Sounds simple, right? Actually, it is. Plus, using less salt can actually improve driving conditions.

Smart salt spreading technologies, which have been effectively used since the 1970s throughout Europe in countries with heavy snowfall, make it possible. At the heart of Europe’s success is the use of a pre-wet 70:30 ratio of granular salt to liquid. Although many DOTs in the U.S. currently use some type of pre-wet mixture, typically around 95:5 (5% brine), their performance results do not begin to mimic those of a more saturated mixture.

Data presented at the 2018 International Winter Road Congress in Poland, in fact, demonstrated that a 70:30 pre-wet ratio (30% brine) does a better job of melting ice, while also using 30% less salt. Such results are confirmed by an array of other sources, including the Salt Institute, which reports that pre-wetting reduces salt application rates 26-30%. ClearRoads, a research consortium comprised of state DOTs, published research results that proved pre-wetting rock salt provides 20-33% material savings.

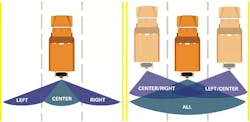

The superior melting capability is partially a result of more salt staying on the road. A 2012 Michigan DOT Bounce and Scatter study confirmed that sufficient pre-wetting keeps 30% more salt on the intended surface. Drier salt, in contrast, is more likely to bounce or be blown off to the side of the road or be pushed off as a result of traffic. Figure 1 compares the cost savings based on the average speed of the spreaders (with 35 mph serving as the industry standard).

In addition to keeping more salt on the road, the liquid contained in the 70:30 pre-wet mixture jump-starts the melting process, improving traction in as little as 10 minutes and sustaining a superior grip rating up to four hours after application, according to data presented at the 2016 EUnited ME conference in Munich.

So what does a 30-35% salt reduction look like in terms of budget dollars?

Consider the following DOT example for Ohio for the 2015-2016 winter season: If 1,638 salt trucks dispense 545,000 tons of salt at a conservative cost of $62 per ton, the total cost paid in rock salt per year is $33 million. Assuming a smart spreader savings of 35%, the Ohio DOT would realize an annual salt cost savings of more than $11 million.

It is easier to compute the savings for a specific DOT or municipality by breaking down these numbers per truck and then multiplying by the total number of trucks in the fleet. Working from the above example, 545,000 tons of salt divided by 1,638 trucks equals roughly 333 tons of salt applied per truck. At a conservative average of $62 per ton, the cost of those 333 tons is $20,646. Now consider a salt savings of 35%. That’s a savings of 116 tons which totals $7,192 in annual savings.

Considering the average life expectancy of a quality spreader is 10 years minimum, that is a lifetime material savings of $71,920 per truck, not including any subsequent savings in labor time.

Even allowing for the industry standard upcharge to replace a traditional spreader with one featuring smart salt spreading technology (complete with the high-capacity pump needed to produce 60 gal of brine per ton to reach the 70:30 pre-wet ratio), return on investment can be realized in only a few years, depending on region and actual usage.

Of course the real value of today’s smart salt spreading technology is not simply measured in budget impact, but rather in safer roads and less damage to the environment.