Sustainable brownfield development for a growing community in Washington State

By: Freeman Anthony

The city of Bellingham, Washington, is a growing community in the northwest corner of the U.S. along the shores of Puget Sound and the Georgia Strait, two major inland areas of the Pacific Ocean.

As this area developed from the late 19th century through the early 1900s, it became a regional hub of the timber and agriculture industry. To support its marine connection, Bellingham’s waterfront was filled and dredged to provide over 200 acres of marine industry that supported many of the area’s economic engines. Over the years those industries have had their rise and fall, along with changes in regional freight behavior that finally led to the closure of the Georgia Pacific paper-plant operations in the early 2000s. This forecasted event heralded in years of planning and discussion on how to manage the former industrial plant site given a history of contamination and its proximity to the rest of Bellingham.

The site property was formally purchased by the Port of Bellingham, and with that purchase came all the related environmental liability. The Port worked directly with city elected officials and department heads to reach out to the community for input on the myriad development options in play, eventually landing on a proposed street grid, development standards, zoning areas, and development phase plan. This included an agreement for the city of Bellingham to foot the bill for primary roadways and site access within the waterfront district. The proposed main roadways through the site, Granary Avenue and Laurel Street, would need to be built to facilitate both private development and public access, carefully consider the site contamination issues, and be reflective of community values all at the same time.

Following a lengthy process by the Port of Bellingham to demolish most of the existing plant buildings and clean/cap the primary portion of the former mill site, the city was deeded right-of-way to move forward with the construction of a half-mile roadway that would open up over 1 million sq ft of commercial/residential development along with connecting to major waterfront arterials and providing the public with access to a new waterfront park. To ensure that the new roadway not only provided site access but was built to a high social, economic, and environmental standard, the city elected to seek Greenroads certification as the design was developed. This would push the project design to a higher level of sustainability in all facets of both design and construction. For the uninitiated, the Greenroads rating system provides a third-party review and certification (similar to the LEED system) for transportation projects to confirm a higher level of sustainability than conventional projects. The city of Bellingham is now very familiar with the system given its previous certified projects and inclusion of the standard in its comprehensive plan. The city registered the project in 2016 and is currently completing the process of applying for certification.

Challenges of Sustainable Development

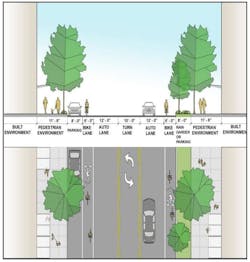

The roadway included public, private, and district-specific utilities, a new public railroad crossing (including new subgrade utilities and the crossing itself), new marine outfall, separated cycle track, potable and non-potable water systems, LED lighting system, and robust street landscaping. In addition to the primary project scope, the project team coordinated with the Port of Bellingham to allow outside contract work including the installation of a district energy system and high-speed fiber conduit system, which added complexity to scheduling.

The previous clean-up work and remaining capped contamination required the project team to work with consultants and the Washington State Department of Ecology to ensure that exported soils, groundwater, and stormwater were fully tested before removal from the site and rigorous protections were implemented during the process. Unforeseen contamination and subgrade utilities were discovered at many points during the process, which required a routine communication protocol along with safety measures and added piping to allow historic site drainage to continue to function around the new utilities and surface improvements.

To limit off-site materials hauling, most hardscape on site was recycled and used for site fill and strategically located under site finishes that would meet the cleanup requirements for site capping. Overall more than 10,000 tons of asphalt and concrete were ground up on site and placed, which greatly reduced delivery emissions and the costs of testing and appropriate off-site disposal. To further utilize recycled materials, imported subgrade fill included crushed recycled glass, and the curb/gutter and standard sidewalk constructed on-site (batched off site) required the use of recycled materials for the coarse aggregate components.

In close proximity to the site was an industrial waterline running directly from the city’s water reservoir to a nearby Puget Sound Energy gas-fired turbine generating station. To increase utilization of this non-potable water source and reduce on-site potable water consumption, a separate non-potable water system of purple-pipe was installed to provide irrigation water to the waterfront district service area. This will lower power consumption at the city’s water treatment plant, and is less costly than standard treated water, saving on utility costs for both the developers and the City Parks Department. Installing the system allows the overall development to meet water conservation requirements put forth in the sub-area plan.

The project also coordinated with the Port of Bellingham to install a district energy system consisting of insulated steel pipes, roadway crossings, and services for a centralized heating system. This system is being developed for the site by the Port of Bellingham and hopes to eventually use waste heat from the adjacent power plant or sewer/geothermal sources to supply residential and commercial properties, lowering the site’s carbon footprint substantially. The new stormwater main and outfall have been sized to allow for up to 20 cu ft/sec of additional discharge from a small hydroturbine system that has been proposed for the site. Installation of the 42-in. outfall and valve was highly technical, as it was constructed under an existing wharf next to a functioning pump station and legacy site drainage pipe with potentially contaminated flow. The new stormwater main utilized an existing outfall in tandem with the new outfall to decrease the required size and limit impacts to the tidal zone and marine life.

At the surface level

The surface improvements include a wider-than-typical street right-of-way to increase space for pedestrian flow, allowing for the city’s first separated bicycle track as well as space for lined bioretention facilities at every block. The stormwater from the site is treated to an enhanced level before being discharged into the Bellingham Bay. Plantings specified for both the bioretention and landscaping were native, drought-resistant, and low maintenance. The northern connection to existing roadways includes the first bike signal in the town to allow cyclists to enter the site directly onto the cycle track without having to navigate lanes dedicated to automobile traffic. The dedicated bicycle turn pocket was constructed right next to an active BNSF mainline just out of the railroad right-of-way. This work, along with the quiet-zone compliant crossing and four large bore casings under the railroad, required extensive coordination with BNSF safety, construction, and permitting personnel.

To enhance the pedestrian experience, the design included raised crossings, precast concrete street furniture, and pigmented/exposed aggregate finishes. The improvements are simple and cost-effective while increasing the experience at the site. Lighting installation throughout the site employed both 30-ft poles at the intersections and 18-ft pedestrian scale poles throughout the corridor for a more approachable feeling experience. The city is committed to making the street itself an enjoyable experience and destination for the public.

Progress report

Since the construction of the roadway and adjacent city park, the area has been abuzz with activity. A yoga studio has opened in one of the site’s repurposed historical buildings, and many locals of all ages use the park and roadway daily for recreation and access. A ‘pump-track’ mountain bike park has also been opened on the inland side of Granary and Laurel and continues to be a major public draw to the area.

The ongoing Greenroads certification process includes the gathering of construction data to calculate overall recycled material use, emissions, light pollution, and water-use reductions amongst many other indicators of project sustainability and performance. This effort is evidence of the city’s commitment to building the best, most sustainable infrastructure it can. The Greenroads system also considers project construction impacts, resilience to climate change, outreach efforts, environmental permitting considerations, light pollution, and even unique components such as the district energy system in assessing performance. These components all support city and community values.

The entire project was years in the making, given the extensive public process and applicable regulations for such a site. The location had historically been used for industry, meaning public access had always been limited. Now, however, it is not uncommon to see kayakers pulling up on the beach, commuters using the dedicated cycle track, runners on their early morning routine, kids at the park, or bikers practicing their jumps—all of which is indicative of a successful project in the eyes of the community. Thoughtful engineering and well-executed construction has paved the way for a sustainable modern waterfront district consisting of roadways and facilities for all, built with recycled materials, over a historically contaminated site.

About The Author: Anthony is project engineer with the City of Bellingham Public Works Department and chair of the Greenroads Foundation Board of Directors.