By: Bill Wilson

What was left of the north section just laid there being poked and prodded.

Ten days removed from glory, five from tragedy, the accused segment of the pedestrian bridge at Florida International University (FIU) in the city of Sweetwater laid lifeless on Southwest 8th Street on March 20. A mini-excavator armed with a concrete breaker tapped at specific sections under the direction of a team of National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigators. From the moment the NTSB arrived on the scene the focus was on a diagonal member of the bridge at that north end of the structure. According to dashcam and surveillance videos, workers were seen conducting what appeared to be post-tensioning with the tubular piece of steel just prior to the collapse that killed six drivers stopped at a red light on Southwest 8th Street on March 15. Another 10 people were injured; the main span of the bridge was lifted into place on March 10.

“Construction crews were applying a post-tensioning force that is designed to strengthen the diagonal member,” Robert Accetta, a member of the NTSB investigative team, told a group of reporters on the site of the collapse the night of March 16.

The NTSB has confirmed that workers were adjusting the tension in two tensioning rods at the north end of the span when it collapsed. The same procedure was done on the south end of the span a couple days before.

“This will be a very complicated and very extensive investigation,” added Robert Sumwalt, NTSB chairman.

For the first time in U.S. history, a bridge failure claimed the lives of private citizens before it actually opened. Back in 1982, the Cline Avenue Bridge in northwest Indiana collapsed before it was baptized by traffic, killing 14 workers.

Once the NTSB finishes the report on the wreckage of the FIU pedestrian bridge it will be delivered to a four- to five-member board for deliberation, and findings of recommendations will be issued.

“We want to look at how the contractors identified the risk and mitigated those risks associated with the construction of this bridge,” said Sumwalt.

Miami-Dade first responders attempt to rescue any survivors after the FIU pedestrian bridge came down onto traffic stopped at a red light on Southwest 8th Street. The failure was the first in U.S. history to kill citizens before the bridge opened.

Proud moment was just that—a moment

A little over a week prior to the NTSB autopsy of the northern section, the bridge was at the center of celebration. FIU’s Accelerated Bridge Construction (ABC) University Transportation Center is known worldwide for its research with ABC, and on March 10 the design-build team of the new pedestrian bridge, MCM and FIGG Bridge Group, lifted a 174-ft, 950-ton section of the span, rotated it 90° across the eight-lane Southwest 8th Street and set it in place. The feat marked another first in U.S. history—it was the largest section moved by self-propelled modular transporters. It was ABC in its finest form; installation of the main span was installed in just a matter of hours.

“FIU is about building bridges and student safety,” said FIU President Mark Rosenberg on March 10. Rosenberg declined to be interviewed by Roads & Bridges magazine following the collapse. The university did release a statement offering its condolences to the victims’ families and promising to cooperate with authorities. “This project accomplishes our mission beautifully. We are filled with pride and satisfaction at seeing this engineering feat come to life and connect our campus to the surrounding community where thousands of our students live.”

The primary mission was to keep students safe when crossing Southwest 8th Street. University housing is on the north side of the thoroughfare, and in August 2017 a student was killed trying to cross.

On March 10, a 174-ft, 950-ton section of the FIU pedestrian bridge was lifted into place.

A non-redundant failure

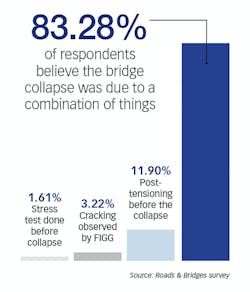

Not long after the FIU bridge—a non-redundant structure—fell onto traffic, speculation of the cause of the collapse was spinning all over the internet. Florida Sen. Marco Rubio tweeted hours after the fatal accident that crews were performing post-tensioning before the failure, a claim which was confirmed by the NTSB during the press conference on March 16.

The Happy Pontist, a well-known blogger who is a bridge engineer in the United Kingdom, wrote an in-depth review of what happened and what might have been the cause of the collapse. Like the NTSB, he focused on the dashcam and surveillance videos.

“In the video, it can be seen that if the truss is conceptualized like a girder, a global shear failure occurs around the position where work is taking place,” the Happy Pontist noted. “Shear in a truss is carried by alternating compression and tension in the web members, so it is possible that the overall failure was caused by failure of a single web member, or by failure of the connecting node.

“It appears from the videos that the second triangular frame from the left (upward-pointing, directly below the crane) deforms, with all other triangles retaining their shape,” he continued. “The very first (downward-pointing) triangle on the left is largely non-structural: The vertical is just there to support the future bridge pylon, while the horizontal upper member in this triangle is just there to carry the upper pre-stressing tendons to their anchorage.”

“I was not surprised to read about another bridge collapse,” the Happy Pontist said, responding to email questions by Roads & Bridges. The Happy Pontist wanted to remain anonymous. “The statistics show that bridges collapse often, and there’s plenty of evidence internationally that the construction phase is a frequent time of failure.”

At press time, nobody knew who was to blame, but there was plenty of finger-pointing by those involved in the project. Just over 24 hours after the collapse, the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) revealed the span’s designer, FIGG Bridge Engineers, contacted an employee at the state agency two days before the fatal fall and left a voicemail regarding cracking observed on the north end of the span.

“We’ve taken a look at it and . . . obviously some repairs . . . will have to be done,” FIGG Bridge Engineer W. Denney Pate said in the message he left, “but from a safety perspective we don’t see that there is any issue there so we’re not concerned about it from that perspective. Obviously, the cracking is not good and something is going to have to be . . . done to repair that.”

According to FIU, FIGG, MCM, FDOT and the university met for two hours the morning of the day of the bridge collapse and determined the cracking did not put the structural integrity of the bridge in any danger.

The NTSB is not sure if the post-tensioning that was being conducted on the north section of the bridge was because of the concern about the cracking.

FDOT claimed it played more of a supervisory role on the project, and outlined its responsibilities in the wake of the tragedy. The agency was in charge of issuing a permit for traffic control when the span was moved into place on March 10 and conducted a routine preliminary review to ensure the project complied with the terms of the agreement with the state. It also authorized FIU to utilize the aerial space above the state road to build a structure, but placed the responsibility of inspection and maintenance on the shoulders of the university.

The state agency also faulted FIU when it came to a required independent, secondary design check. FIU chose Louis Berger, which FDOT claimed was not on the pre-qualified list. FIU refuted, saying all of its “contractors were on the pre-qualified list.”

Questions also were being asked as to why the FIU design-build team decided to build a non-redundant structure as opposed to one that is redundant, where if one member of the bridge fails the rest of the structure will prevent it from collapsing.

“Even for simple bridges, there is no reason to build a non-redundant design,” Anil Agrawal, professor of structural and bridge engineering at the City College of New York, told Roads & Bridges.

Open for danger

So why was Southwest 8th Street open to traffic the day of the collapse? In an email response to questions from Roads & Bridges magazine, FDOT said it was not made aware that the FIU design-build team was conducting any kind of stress testing of the bridge following installation and had no knowledge or confirmation from FIU’s design-build team of stress testing occurring since installation.

“Per standard safety procedure,” FDOT told Roads & Bridges, “FDOT would issue a permit for partial or full road closure if deemed necessary and requested by the FIU design-build team or FIU contracted construction inspector for structural testing.”

FDOT said it did issue, following a request from the FIU design-build team, a blanket permit allowing for two-lane closures effective January through April of 2018, but “at no time, from installation until the collapse of the bridge, did FDOT receive a request to close the entire road,” FDOT told Roads & Bridges.

“Any kind of work . . . even post-tensioning which is always risky because if you apply too much force there is a risk of damage . . . you have to make sure the accepted protocol is in place,” said Agrawal. “When they are doing a simple thing like bridge inspection, when there is a worker working on a bridge or doing an inspection, they tend to block the road for their personal safety. When you have a bridge in place that is not fully secured and work is going on they certainly should have closed the road to traffic.

“Either they were too confident that nothing would happen or they really did not analyze the risk very well.”

“I would say should you be doing post-tensioning on any bridge when traffic is flowing underneath?” John Stanton, a professor at the University of Washington, told Roads & Bridges. “I think it is a questionable thing to be doing.”

At press time, the family of a truck driver, Rolando Fraga, had filed a lawsuit against the contractor, MCM, and the designer, FIGG Bridge Engineers. The family seeks unspecified damages for Fraga’s lost income and for pain and suffering.

ABC not a suspect

As far as the future of ABC in the U.S., all the experts Roads & Bridges talked to following the collapse stressed that the cause of the accident had nothing to do with the method.

Agrawal does not believe the FIU bridge collapse was the fault of ABC, but did stress the process takes a higher level of expertise.

“If you plan very well, you understand the process, you have enough level of expertise, there should not be an issue,” he said. “This is not an example of the failure of ABC, it is an example of the failure with risk management and doing their due diligence and good quality control in design and construction.”

Stanton agreed, and stressed it is important to dispel the notion that ABC as a process is in any way dangerous or inherently flawed.

“I don’t think the process is flawed,” he said. “There may be some details of the way it was done that were not done as well as they should be. If you make a Boeing airplane and you make a mistake when you are building it is going to fall out of the sky and you are going to kill a lot of people, and that would be very unfortunate. It doesn’t say airplanes as a species themselves are inherently suspect because they are not.

“[FIU] has an ABC center there and I would hope the ABC center will be able to weather the politics of this particular storm and come out and get beyond it and say ABC has a future; we need to look forward, not backward,” added Stanton.

Will FIU build again?

When the NTSB investigation is complete, will FIU consider rebuilding a bridge over Southwest 8th Street? After all, student safety is still at risk crossing the always-busy eight-lane road.

“The primary reason they started constructing the bridge was because somebody died,” said Agrawal. “They will still build a bridge, but it may be more of a traditional approach to it. I bet they will build a bridge there.”

“From what I have read it is a pretty dangerous intersection,” Brian Deery from the Associated General Contractors of America, told Roads & Bridges. “I think they are either going to build another bridge or maybe build an underpass, but that will be expensive. It is going to be a while before they get to [building again].”

About The Author: Wilson is editorial director of Roads & Bridges.