By: Sherry E. Little

Those who closely track recent development of new public-private partnerships (P3s) in the public-transportation sphere can be forgiven for stifling a yawn.

There is no doubt that a profusion of private-equity funds and pension funds are available for these purposes—recent estimates are pegged north of $200 billion. Managers of these funds are indeed actively seeking to invest in the development of infrastructure in the U.S. because of the long-term yield and stability that those investments tend to bring in similar markets in Canada and the U.K. The market is flush with opportunities; the supply of private-sector capital is available.

There is no argument that our public-transportation network is in dire need of both investment and reinvestment. The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) helpfully produces an analysis of the quality and performance of America’s infrastructure and assigns a corresponding letter grade to each type. The 2013 Infrastructure Report Card paints a troubling picture. Across all sectors, ASCE estimates the amount of investment needed to get our system to a state of good repair by 2020 is in the neighborhood of $3.6 trillion, while public transportation, specifically, fared poorly with a grade of D.

The last few surface-transportation authorization bills passed by the U.S. Congress have not kept pace with demand, and thus the public-funding gap has widened. In fact, the 18.4-cent gas tax, which funds both highway and transit investments, is not indexed to inflation, and has not been raised in 20 years.

No additional resources aside from the gas tax have been committed or even identified, and resultantly, the Highway Trust Fund has limped along, primarily thanks to infusions from the general fund of the U.S. Treasury. The Highway Trust Fund is insolvent and—absent any new revenue—will completely exhaust its cash balance in FY 2015, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

So what does it say about this market that at least $200 billion in resources are available and not being otherwise utilized, and mounds of independent data from ASCE, the American Public Transportation Association and others reveal a dire need for those resources?

Given that the bulk of my career has been in innovative transportation financing at a time this market is morphing, I come at this issue with the benefit of having seen it from a number of different perspectives. During my 15 years as a staffer in the Senate, among other things, I drafted the Public Private Partnership Pilot Program (Penta P) for inclusion in SAFETEA-LU, the surface-transportation bill that was the law of the land from 2005 to 2012.

This provision was designed to incentivize transit agencies to seek innovative ways to work with their private-sector partners in the financing of their systems and to find opportunities for requisite risk transfer; that is, to transfer some risk from the public sector to the private sector.

Penta projects

After departing the Senate to serve as President George W. Bush’s deputy federal transit administrator, then acting administrator, my top priority was the development of the regulatory structure of Penta P. That effort resulted in three projects that sought to pioneer risk transfer and private investment, the most shining and successful example of which is the Denver Eagle’s design-build-finance-operate-maintain project.

We also made it a priority to reach out to the industry, with help from the National Council of Public Private Partnerships. In workshops nationwide, we brought together both the leadership at public-transportation agencies as well as Wall Street private-equity firms. The feedback we received was very positive, indicating that the workshops had helped to determine the impediments to P3s and what incentives state and federal legislators might offer that could actually remove the impediments and motivate the industry.

In my current capacity as a partner and co-founder of Spartan Solutions LLC (based in New York and Washington, D.C.) my partners and I advise public-transit agencies pursuing a P3 process to meet their infrastructure demands, such as the high-performing and innovative Dallas Area Rapid Transit, and well-regarded private rail construction interests bidding on P3 opportunities, such as Herzog Construction Corp. out of St. Joseph, Mo. With this experience under my belt, I offer the following observations:

Both parties should do their own thing

Allow the respective parties to do what they do best. As stewards of taxpayer dollars, public servants are justifiably cautious about taking risks and inherent in the P3 process is risk transference, in one form or another. The risks to the public for a project gone awry are, if not greater in magnitude, certainly more transparent to the public and to political leadership. Off the top of one’s head, it may be a challenge to name projects that have been delivered on time and on budget, but Boston’s Big Dig and the federal loan guarantee for failed Solyndra consistently made national headlines.

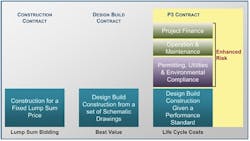

Caution is both advisable and understandable. However, when the public sector holds the reins too tight, it limits the ability of the private sector to innovate and reap the benefits that come with that innovation. Certainly, the public partner should and must provide proper and continual oversight through the planning, construction and life of the project. In the planning and development of the project, the public partner retains the responsibility to specify performance-based outcomes, set general safety standards to protect the riding public and closely monitor expenditures and the draw-down of funds. Beyond that, it is counterproductive for the public partner to specify all details of the project, right down to the placement of signage and the locations of waste receptacles in stations.

It is not realistic to expect that the public partner can specify every nut and bolt, and then expect the private sector simply to perform a project less expensively. The private sector can only create efficiencies if it is allowed to innovate. A better approach might be one where the public partner requires that a system be built that carries X riders from Point A to Point B within specific headways and with certain performance requirements, including safety, maintenance and the like. This allows the private partner to innovate regarding design and construction, as well as vehicle design, system maintenance and operations, to accept risks for subpar performance and to be rewarded for meeting and exceeding the performance requirements.

Ready to go private

Use P3s to advance projects slated for reinvestment, upgrade or state-of-good-repair efforts. There is no shortage of these projects on the books slated for reinvestment, upgrade or state-of-good-repair efforts. They have the potential to make good targets for innovative finance P3 efforts. There are two reasons for this, aside from merely the profusion of opportunities. First, they are often within the existing NEPA footprint, and thus the private partner may have reasonable assurances that the environmental work will not be long, protracted and expensive. (Private partners are not eager to have their funds tied up indefinitely due to costly litigation caused by endangered species discovery, historic-preservation issues, etc.).

Second, with state-of-good-repair projects, it is often easier to estimate the benefits, because the transit project has already been performing in the service of the agency. Presumably, with a rail-rehabilitation project, the ridership has been charted and tracked over the course of a number of years that led up to the need for the reinvestment. Thus, a private partner might be more comfortable with the structure of a particular availability payment or perhaps even be willing to take a limited ridership risk.

Private partners can benefit too

Private partners—be they construction interests, passenger-rail operators or financial investors—can benefit from being invited to participate in solving a transit agency’s infrastructure needs and having incentive to take the risk that is inherent in a P3. Not every transit agency or state DOT that envisions a P3 has a clear picture of how to go about it, which risks they are comfortable transferring or whether political leadership will embrace the concept. Private partners are cognizant of those factors and sometimes need convincing that, in terms of determining whether the climb is worth the view, the public partner is serious about a P3 or innovative finance approach. They often need reassurance that the public partner is not merely testing the waters by soliciting participation from the private sector without any intention of truly following through with a robust solicitation.

Often, private partners gain comfort if the transit agency or state DOT is forthcoming in sharing information about the proposed project, makes it available to answer imperative questions about tolerance for risk transference, and clearly explains its expectations regarding the benefits they need to justify a P3 approach. Additionally, if the public partner offers a stipend to the prequalified private offerors responding to a solicitation, not only would it (slightly) defray the costs of preparing a comprehensive and responsive solicitation, but it also would telegraph the agency’s seriousness to consider such an approach, essentially putting their money where their mouth is.

Likewise, public partners can benefit from incentives that are made available to them. The Penta P approach, referred to earlier, attempted to accomplish just this. By providing transit agencies relief from some specific elements in FTA’s complex and highly sought after New Starts grant process, Penta P sought to entice public partners to think creatively and team with private partners in ways that were mutually beneficial.

The same concept can be used with other federal grant programs; for example, the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act program (TIFIA) provides loans and loan guarantees for U.S. DOT-eligible projects. Currently four P3s are progressing through the TIFIA process and eight of the 31 projects that have submitted letters of interest since the passage of MAP-21 envision using a P3 delivery mechanism.

Since MAP-21’s four-fold increase in TIFIA’s lending capacity was made available, perhaps a specific portion of those resources could be made available exclusively for projects that employ a P3 approach, thus driving decision makers to the TIFIA pool of money. Alternatively, the U.S. DOT could prioritize those projects seeking funding from sources that are typically used as P3 repayment mechanisms, such as parking revenues, naming rights and value capture.

Financial horizons

Finally, although the federal financial landscape for transportation appears bleak, that creates historic opportunities for P3s, owing to the gap in taxpayer funding. In the meantime, private-sector investment is no substitute for sustainable, continuous, predictable federal and state funding. Even with the abundance of private equity dollars available for these purposes, the federal government cannot and should not abdicate the responsibility for expanding and maintaining infrastructure to the private sector. The private sector needs assurances that the projects they are investing in are meeting the needs and priorities of the community and that the public sector will assume a long-term duty to maintain them.

Similarly, the public sector requires the kind of long-term, sustainable and predictable resources to ensure capital planning. The duty of our government to assist in getting people to jobs and goods to market cannot be passed off to a private party. P3s are a tool in the toolbox rather than the silver bullet to solve our infrastructure woes.

Although the performance of U.S. public-transportation P3s of late has admittedly been lackluster, there is promise on the horizon. Advocacy groups such as the Association for Investment in American Infrastructure (AIAI) have undertaken worthwhile activities to bridge the gap between resources available and demand for those resources. AIAI’s leadership comes from many of the most active construction interests in the country. AIAI’s core mission is to create more opportunities for P3s in the U.S. With efforts geared toward increasing awareness of P3s, establishing clarity in procurement procedures and seeking to foster a more robust pipeline, they have an ambitious agenda.

In addition to outside advocacy groups, the U.S. Congress also now has a Congressional Caucus on P3s. This group of Congressional members aims to not only increase awareness of P3-related transactional successes, but also to develop agreement on legislative approaches that may foster more opportunities.

An increasing number of states are passing versions of P3 legislation. And although the market could use a goosing, a few states and localities have indicated interest in developing alternative approaches, including Chicago’s Red Line Extension, Denver’s North Metro Commuter Rail Line and Maryland’s Purple Line, all of which are in the early planning stages. If you’ve seen one P3, you’ve seen one P3, as they all differ in risk transference and financial composition, but the market is certainly ripe for opportunity.

About The Author: Little is a partner in Spartan Solutions LLC, Washington, D.C.