By: Peggy Tadej

In an effort to reduce vehicular congestion on I-95, the Northern Virginia Regional Commission (NVRC) has signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOUs) with northern Virginia’s military installations to offer transportation demand management (TDM) solutions to the hundreds of Department of Defense (DoD) agencies that work in and around the region.

Through the MOU partnering, NVRC has created on-site commuter centers to educate employees about their commuting options. TDM on military installations has unique challenges that make existing methods ineffective in contributing to the reduction of single occupancy vehicle (SOV) use in employee commuting. These challenges include security concerns and fluctuations in management (base command changes every few years). Additionally, traditional TDM incentives have not proven successful in changing commuting behavior with the military, DoD civilians or contractors. Those working at these sites are non-traditional stakeholders in that they are often new to the area and unfamiliar with existing options that the region has to offer for commuting to work. To consider alternatives to SOVs, base employees need to be assured that their commuting solutions will take into account the flexibility their schedules require.

The DoD is not merely a singular employee in northern Virginia; it is a critical component of the region’s economy. With over 115,000 on-site employees, many aspects of base logistics have resounding effects on the whole region, including transportation, notably massive traffic congestion along the I-95 corridor. In the absence of adequate transit options and DoD funding dedicated to transportation, other resources must be employed to curb the 83% SOV rate of DoD employees commuting to the bases every day. By addressing the commuting issues of base employees and working toward a reduction in SOV travel, everyone driving during peak hours on these crowded roadways can expect to see a reduction in congestion.

The military presence

During BRAC 2005, northern Virginia experienced the most dramatic shift in the composition of its military installations of any region in the U.S. This created many additional transportation issues in an area that was already plagued with major problems of traffic congestion and delays. The Texas Transportation Institute’s 2015 Urban Mobility Report ranks the Washington, D.C., metro area No. 1 in yearly delay per auto commuter (82 hours), fuel wasted per peak auto commuter (35 gal), and cost of delay per auto commuter ($1,834).

The military presence in northern Virginia starts with the Pentagon and Joint Base Myer-Henderson Hall (JBM-HH) located at the top of the region, surrounded by Arlington County. Fort Belvoir is located to the most eastern part of the region in Fairfax County and includes the Mark Center and the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency. Marine Corps Base Quantico (MCBQ) is located at the southern end of the region in Prince William County. The military bases located outside the beltway suffer from a lack of public transit options. About 231,000 cars per day travel along I-95, with about 110,000 people traveling to one of the three regional military installations. Approximately 40% of the drivers on this major corridor are DoD personnel and contractors going to the military bases, with 56,000 cars per day going through Fort Belvoir, 42,000 cars per day going to MCBQ, and 12,000 cars per day going to the JBM-HH gates.

According to Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments’ Transportation Planning Board, which conducted the BRAC/Federal Employment Consolidation Impact Analysis Travel Monitoring Report, the proportion of single-occupancy trips compared with multiple-occupancy trips for both Fort Belvoir and Quantico was at 83% versus the proportion at all regional monitoring sites, which was 76%.

A contributing factor for the high SOV rate among base employees is that neither infrastructure nor individuals could easily adapt to the new traffic patterns in the region created by BRAC. The report highlights this issue: “In general, most of the BRAC and consolidation locations are difficult to serve with transit, and a point compounded by the regional shift in work locations due to the BRAC actions without a corresponding shift in locations of residence of those workers. Base Transportation Management Plans (TMPs) attempt to create modal shifts in the installation workforce by offering alternative modes of transportation, restricting parking, etc.” The BRAC moves took place in September 2011; however, many of the resources set up by BRAC to facilitate the transition were lost as a result of sequestration, making the transition to TMP strategies that much more difficult.

As a result of these transportation pressures, all modes are nearing capacity, particularly I-95, and including the major surface transportation arteries, Virginia Rail Express (VRE) that stops at MCBQ and the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority’s (WMATA) Metrorail system. Moreover, regional transit alternatives such as those provided by commuter bus agencies are also experiencing demand in excess of their ability to provide service.

With the 2005 BRAC relocation of 22,000 defense personnel and contract workers from office buildings throughout the National Capital Region (NCR) to just five secure facilities clustered along the I-95, traffic impacts have been well documented by studies completed for each installation.

Economically crucial

It is often difficult to consider military installations as part of the community or an important part of the state. However, the current national economic state is dependent on a sustained military presence. If traffic congestion begins to undermine the advantages the military finds in the region, economic prosperity is in jeopardy.

Vulnerability stems from the fact that Virginia holds:

- The largest concentrations of military installations and agencies in the U.S.;

- The most federal procurement spending, defense and non-defense, going to any state;

- The largest assemblage of federal civilian and DoD workers in the U.S.;

- The largest assemblage of military headquartered command functions, including the Pentagon, Defense Logistics Agency (DLA), Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA), Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, and numerous other defense agencies; and

- One of the largest, best-educated pools of private-sector contract workers providing goods and services paid for by the U.S. government.

No other state can compare, nor does any other state have a larger percentage of its economy tied to military spending than Virginia. While the military presence in northern Virginia is not as overtly visible as in other regions, it is an acknowledged driver of regional economic growth and output in Virginia’s Washington, D.C., suburbs. While the workforce engaged in DoD-related activities is disbursed throughout the NCR, large, critical components have been relocated and concentrated onto military facilities along I-95.

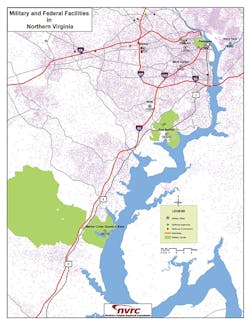

A map of the military and federal facilities in northern Virginia.

Shifting culture

Amongst the challenges of the 2005 BRAC was the transportation upset to the region, but more importantly was a changing culture centered on the SOV. The DoD provides mass transportation benefits to its employees to offset commuting costs and to reduce pollution and traffic congestion, preserve the environment and expand transportation alternatives. Unfortunately, because of the lack of transportation alternatives to the military, only about 7% of personnel from Fort Belvoir receive these benefits. The benefit was paying about $130/month, and when gas prices went down, a decline in alternative transportation use was observed from the bases. This led to 86% of employees commuting via SOVs. Sequestration cut funding for all alternative transportation options, such as the internal shuttles to the Metro. NVRC was able to assist in standing up the Eagle Express on Fort Belvoir in which Fairfax County provides the service from the Franconia/Springfield Metro Station to Fort Belvoir. However, public transit remains inconvenient for the military installations outside the beltway.

Transportation management plans (TMP) created by the bases to mitigate the transportation challenges associated with BRAC were largely abandoned as a result of sequestration. As the bases subsequently experienced a variety of related challenges, base command turned to NVRC for assistance. NVRC has been working with the bases on alternative transportation for the past five years. Other defense communities have adopted our strategies to work with military personnel on their bases. NVRC signed an MOU with Marine Corps Base Quantico (MCBQ), home to 26 separate agencies including the FBI, Joint Base Myer-Henderson Hall (JBM-HH) and Fort Belvoir, which includes the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (10,000 employees), the Mark Center (6,400 employees) and an additional 156 other DoD agencies.

The resulting NOVA Community, Military & Federal Facilities Regional Partnership, formed to support the dialogue between the community and the military installations, has had a positive effect not only between the community and the base, but between the bases as well. Once agreements with Fort Belvoir began to yield positive results, the other bases became engaged. Small steps have been taken and progress has been made. The bases are using these meetings to seek solutions, articulate their needs and request assistance from NVRC. NVRC’s involvement in military transportation began through a grant from the DoD Office of Economic Adjustment (OEA) in which a strategy was devised. A second grant was applied for and received from the U.S. DOT’s Value Pricing Pilot for a Real-Time Rideshare program working with the military installations. Valuable lessons garnered from this initial involvement pointed to a basic lack of knowledge by military personnel of the cost of driving as well as a lack of awareness of the TDM alternatives and of the mass transportation benefit available for DoD personnel. The program objectives were to institutionalize the concept of ridesharing by providing table events at tenant agencies with education and outreach on TDM solutions as well as the benefits of car and van pooling.

Though each base is unique and each agency is structured differently, the message is the same: provide emphasis on offering options for SOV reductions. Custom-tailoring commuter options to address the specific needs of the tenant agencies fulfills the security requirements for that agency since many are in secure facilities. When on-site, employees have the opportunity to sign up for carpools, vanpools, purchase tickets for local and regional bus and rail systems, and become educated on the use of the I-95 Express Lanes. The primary goal is to reduce SOV trips during the rush-hour commute by offering mobility options to improve accessibility to the base facilities.

Communication is key

Central to the concept is the belief that delivering comprehensive transportation services and commuting programs is best performed at the worksite as an integrated service for all employees. As work schedules, employee populations, home addresses, and prevailing traffic patterns change, so do the commuting requirements of a workforce. Creating the culture from within and at a grassroots level creates buy-in by the tenant and the employees. The reason for this embedded approach is that there is no one central way to communicate with everyone on a particular base: you must directly interact with the various agencies and, often, with individual employees to spread a message.

In May 2015, George Washington University’s Trachtenberg School of Public Policy and Public Administration provided a pro-bono evaluation and cost-benefit analysis of the partnership with Fort Belvoir, which tested the hypotheses that the commuter center was affecting decisions on a wide scale. The students identified the institutional barriers (base access, base size and number of tenant agencies) that prevented commuters from fully utilizing the commuter center, and evidence from the surveys show that the incentives are not encouraging people to rideshare.

When asked, respondents said that the money currently offered would be enough to encourage them to rideshare . . . but money isn’t really the primary driver in how they make their commuting decisions. Rather, spatial and time issues predominated, with scheduling problems, inconsistent work hours and a lack of convenient carpool locations being the most frequent responses.

The takeaway for NVRC was: “Our survey results support the idea that no reasonable monetary incentive will significantly change the population that is willing to rideshare and that, rather than spending more money on incentives, NVRC should look towards better tailoring its services to commuters’ needs.”

Building on past experience and the base readiness through the partnership agreement, NVRC partnered with a private-sector vanpool company, vRide. The base TMP requires all agencies in excess of 100 personnel to demonstrate steps toward a reduction in SOVs. Further steps have been taken to work with the individual agencies by promoting the Federal Commute to Work Tax Benefit, which rose to $255 per month. The approach has been to tailor a ridesharing culture to each of the bases and address the unique needs of the individual tenant agencies. Particularly for those agencies that practice the utmost security, this approach of ridesharing from Park and Ride lots to that agency site have proven to work by keeping it at a grass-roots level.

In talking to base personnel, the concept of “slugging” is familiar to those with DoD experience in this region. Many have spent time at the Pentagon, where it is most prevalent. The practice has grown more widespread as a result of the HOV-3 requirement and I-95 Express Lanes, which are open to vehicles with three or more occupants. The Mark Center created an internal virtual ridesharing system that is confined to that agency only. This is the same solution that we are applying to the larger tenants on base. The process started with top management support from the Base Commander and Agency heads. We worked with the director of the agency to build a tenant management team that included personnel from the facilities, security, human resources and IT departments. The Commuter Center provides the outreach, marketing and a volunteer, who helps to internally maintain the system. The tenant management team discussed the parameters of the type of system, how it would operate, the role of the volunteer, and assisted with the messaging and marketing. Various methods of setting up the system included: one agency used the “Group” feature on Outlook and another setup a SharePoint for people to go to connect. Essentially they have a closed LISTSERV that is then managed by a volunteer and supported by the Commuter Center.

The MOU for the public-public partnerships between NVRC and the bases provides the institutionalization of base TDM that is resilient to the fluctuation in command. Today, the current base commanders have been great in allowing us access on the base, welcomed us to attend the monthly partner meetings, and allowed us to give presentations at the quarterly facility meetings in which transportation issues are addressed. This is a repeat lesson learned: that the military functions under a hierarchical system and we have to follow through the chain of command. The Base Commander has opened doors for us with introductions to some of the larger agencies.

These same steps are followed in addressing all the agencies, because once again, following the hierarchy when dealing with the military is the most efficient way to getting results.

Build a ridesharing culture within tenant agencies: It’s well-known that there is frequent relocation associated with life in the military. There are monthly orientations held on base to service all of that movement. Therefore, it is not enough to appeal to individuals to change their behavior, but rather, there must be a change in commuting culture such that newcomers will learn about transportation alternatives before they develop the habit of traveling in an SOV. This requires an intensified effort to propagate our TDM outreach that must be direct and frequent. The targeted campaign is designed to offer a menu of commuting options custom-tailored to meet the specific needs of the agency and the individuals employed by them.

Facilitate flexible ridesharing: Flexibility is a major concern for those considering rideshare programs. Having limited freedom in regards to coming and going from work is very unappealing. To provide an increased level of flexibility, NVRC and vRide have identified a possible opportunity to offer multiple daily vanpool options to individual users. By identifying where we have empty seats on a van, or purposefully leaving a seat or two vacant, we can open up the opportunity for dynamic vanpooling. The vanpools would be set up on an individual account so that riders are able to switch between vans that travel their route at different times of the day.

The takeaway

At the last Transportation Research Board meeting in January 2016, the question was raised as to what made this work in the Virginia region. The answer is that a partnership was built between the military bases and the region as a place to talk about the issues and solutions. Having the MOU with the bases created a lasting relationship. By joining together on a bi-monthly basis the right people were brought to the decision table with the Base Commander and community leaders. When problems arose, the community was willing to explore options. New concepts were devised with the funding from U.S. DOT to implement the dynamic ridesharing that evolved into the current program. The region sees duplication as a compliment and is very involved in the art of the possible with the concept of the “Base of the Future” being operated by the community.

About The Author: Tadej is the director of Military Partnerships for the Northern Virginia Regional Commission.