By: Michael Boone

Globally, those engaged in the ongoing dialogue about infrastructure are asking challenging questions: What infrastructure is deficient? How should infrastructure owners deploy the resources, authority, and responsibility they steward? How can and should owners assess, pay for, and support current, changing, and future needs?

With technological innovation and infrastructure need outpacing funding, now is the time to rethink and refine answers to these questions and to define what the larger term “mobility” means, particularly for vulnerable road users. Within the developing narrative of next-generation infrastructure, we have the opportunity to invite different voices and to champion new thinking that addresses the mobility needs of all.

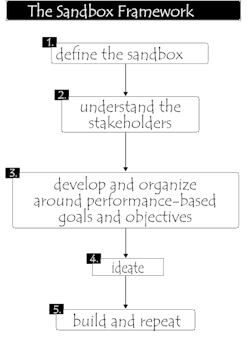

Redefining mobility to meet the needs of everyone requires a systematic, five-step approach.

1. Define the sandbox

Before beginning to architect purpose-driven mobility infrastructure solutions to meet the needs of more people, you must understand the sandbox in context and where it is.

Traditionally, the sandbox has been limited to the physical road itself, the majority of traditional right-of-way. However, mobility is about more than just the road automobiles travel; mobility includes sidewalks and curbs, medians and dirt trails, the streams that intersect with the road, and the airspace immediately above it. Mobility extends beyond the roadway. The horizons of today’s sandbox are broader than what they used to be and are continually evolving. Sidewalks, for example, are becoming a bigger part of the conversation. Sidewalks are paralleling roads where they once did not. Wider sidewalks and trails are checkering mixed-use developments. Pedestrian bridges are connecting residential and employment hubs over busy interstates. Electric scooter and bike riders populate retail and tourist hubs with designated spaces and lanes that allow them to whiz by foot traffic. It is time to understand all of the real estate that is available and use it to foster mobility solutions outside of the roadway.

Broader solutions, however, cannot be implemented without fully understanding the social, political, and economic contexts of the sandbox and those adjacent to it. Questions worth asking include: What are the norms for commuting to work and how did they develop? What unique regulations govern the locality and how do they interplay with state and federal law? What is the time value of money and how do people spend discretionary funds? What is the consumer's understanding and response to these questions?

Knowing where to look to answer questions like these focuses your time and thought in the right areas. To identify gaps in need(s) and solution(s), you must determine what is and is not being done to prevent duplicating or investing time in a problem that already has a functional solution. Understand what physical infrastructure is present, how it works, and how it complements the sandbox; how it was financed, and what condition it is in. For instance, you may research how roads are built, how traffic is controlled on them, how people and vehicles interact on a roadway facility, and identify challenges in design, user interface, or questions related to human factors. It is important to continuously stay abreast of the general practices and innovation within the sandbox to grow and maintain technical grounding. Otherwise, there is a risk of thinking from behind the actual starting line. To begin, start road-mapping ideas by engaging people and ideas that conflict and challenge your thinking and that are established by others.

As you define your sandbox, remember to use understandable language to continuously record your findings, the progression in narrative and lessons learned. This is critical for onboarding and transferring knowledge to new practitioners so that they can jump in on the same page and start from an identifiable point in time. In terms of vernacular, define words frequently and use the same words consistently. Next-generation infrastructure requires everyone, particularly those that contribute in this space, to understand the "who," "what," "where," "why," and "how" of the sandboxes we live in.

Capturing social, political, and economic context reveals sandbox dynamics and informs the development of inclusive mobility solutions.

2. Understand the stakeholders

That said, understanding context is a continuous effort that requires constant refinement. Making that continuous effort is the only way to understand the stakeholders in the sandbox, the individuals you aim to serve. Craft your solution, product, and/or service around them as end users. Target a specific end user or set of users that has some identifiable unmet or poorly met need(s). Recognize vulnerable road user hardship to define transportation mobility where there is lack. For instance, a population of elementary school children may have trouble walking to and from school in an area that has heavy cut-through traffic, or memory-impaired residents of a local assisted living community may struggle to get from point A to point B. The end user(s) may change, but starting with a narrowly defined segment of the population with unmet needs leads to focused solutions. Zero in on and articulate the need(s) facing your identified "who,” and validate your understanding of the unmet need with research. Expand the subject of "who(s)," if needed. If unsuccessful in identifying an end user with an addressable need, refresh your understanding of the sandbox and adjust from there.

In developing the Smart Columbus Mobility Assistance for People with Cognitive Disabilities (MAPCD) mobile application, for example, HNTB worked with the city of Columbus to develop requirements based on the needs of end users. Initially, the team was focused on persons with cognitive disabilities who needed to get from point A to B using public transportation. The team developed requirements for a mobile application to serve those needs, but ultimately grew those requirements to include primary caregivers who needed the ability to track individuals in real-time. Lesson learned: understand the needs of all users as they may not be the same. More about Smart Columbus's Mobility Assistance for People with Cognitive Disabilities can be found at https://smart.columbus.gov/projects/mobility-assistance-for-people-with-cognitive-disabilities.

3. Develop & organize around shared performance-based goals and objectives

Step three in the sandbox framework is developing and organizing thinking around shared performance-based goals and objectives. Without predefining the mobility solution itself, write out what needs must be addressed.

In thinking through needs, start by tying what is known through data. For example, if charged with increasing the number of cyclists commuting to and from work by 25%, list the challenges that hamper or discourage this goal and the related outcomes within the sandbox. In pursuit of this goal, other related questions to study include: How crowded is the area? What infrastructure is present to support cycling? How far does the average worker live from work? Once challenges and threats to goals and objectives have been identified, think through who to partner with for messaging, operations, and financing. Frequently, others can be identified that not only have shared goals and objectives, but have similar and identical values, mission, and vision that overlap and align with yours.

HNTB supports the Florida DOT (FDOT) and its partners as needed to analyze data and information (safety and context solutions) around the Safe Mobility for Life (SMFL) Program. Through the SMFL Coalition, FDOT and its partners developed a comprehensive Aging Road User Strategic Safety Plan that is integral to the state's larger transportation plan. The state of Florida estimates that its population of persons aged 65+ will grow from just under 20% to more than 25% within the next 20 years. With this statistic in mind, Florida's public and private enterprises implement and develop resources to support 21 coordinated objectives in SMFL within six integrated focus areas. Working together, SMFL will improve the safety, access, and mobility for Florida's aging population across modes and practice. More about the Safe Mobility for Life can be found at http://safemobilityfl.com.

4. Ideate

Steps one through three create the platform for generating ideas. When thinking about mobility globally, most tend to jump straight into step four, ideate. During ideation, think through scenario-based use cases for end users and build from what you have. For instance, ask “how might we augment signing and lighting for elderly visitors exiting from a light-rail platform to visit a newly opened, mixed-use town center?” Scenario-based use cases like this allow beginning with a smaller, more controlled environment and scope. HNTB has found building from existing infrastructure can provide meaningful, incremental improvements with higher potential for success.

HNTB works with infrastructure owners in developing solutions that are designed around scenario-based use cases. HNTB recently worked with the Government of Bermuda in an advisory and design review role during the project design phases for a new airport terminal facility, which included aircraft passenger boarding bridges to enhance passenger circulation and access for those with limited mobility. In Florida, HNTB is also helping oversee and monitor low-speed door-to-door autonomous vehicle shuttle deployment for trips in a private, master-planned retiree community. In the nation’s capital, HNTB worked with the District DOT (DDOT) to optimize timing for high-intensity activated crosswalks (HAWKs) for pedestrians where traditional traffic signals may not be warranted. HNTB worked with DDOT to optimize movement and safety for pedestrians, particularly during peak morning and afternoon periods. More about DDOT's HAWKs can be found https://ddot.dc.gov/page/hawk-signal.

5. Build and repeat

Finally, build and repeat. Keep in mind there are public involvement, funding, and procurement phases before groundbreaking, but delivery comes from the sandbox, not outside of it. Properly identifying an unmet need, connecting it to a goal, and developing a solution for someone who is not currently served or served well in an existing sandbox is worth repeating. Organizing around the sandbox approach can contribute to an inclusive ecosystem that identifies, promotes, and delivers needed mobility solutions for all.

About The Author: Boone is an Intelligent Transportation and Tolling Systems engineer with HNTB, an employee-owned infrastructure firm, and is part of their emerging mobilities solutions and National Priced Managed Lanes teams.