Multimodal intersection and road reconstruction in Boston modernizes a historically transit-oriented community

By: Brian W. Budzynski

The neighborhood of Jamaica Plain in Boston, Massachusetts, has since time immemorial been a locus for public transportation and a dependable thruway for commuters and locals, as well as denizens of Rhode Island, Connecticut, and even New York.

It was one of the nation’s first streetcar suburbs, and today in this one location is the convergence of 11 bus routes, Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor, and the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority’s (MBTA) Orange Line and its commuter line into and out of Boston. When you factor in each of these services, this is the most heavily traveled transit corridor in the entire Northeastern U.S.

However, the existence of a structurally deficient bridge taking traffic over the old MBTA station headhouse had begun to result in less than optimal traffic flow—and more importantly, precluded the development of the overall area as both destination and throughput for daily commuters and pleasure seekers, both of whom lay claim to the area.

As the keystone project of the Massachusetts Department of Transportation’s Accelerated Bridge Program (ABP)—a $3 billion fund set up to address the declining state of the Commonwealth’s bridge infrastructure—the Casey Arborway reconstruction project fulfilled its purpose and duties by eliminating this structurally deficient bridge, and opening up movement within the neighborhood, notably for pedestrians and bicyclists. The overall ABP has led to subsequent projects that have further enhanced the area, including a priority bus lane on Washington Street and the installation of Blue Bikes at the Forest Hills Station, as well as three large multiuse building redevelopments that abut the project. The Casey Arborway is a signature example of MassDOT’s prioritization of transportation benefits for all travel modes, focusing on moving people, not just vehicles.

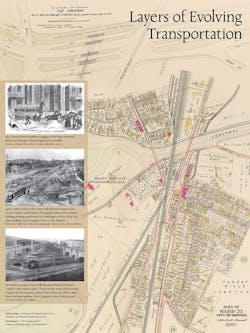

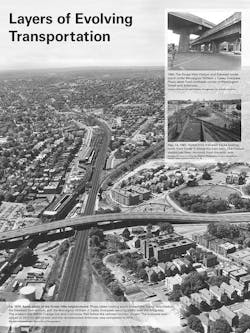

A history of change

“Throughout the entire project, we said we were building a park and roadway, not roads around a park,” Jonathan Kapust, project manager for lead designer HNTB, told Roads & Bridges. “This area has been troublesome for planners for a very long time. Figuring out the best plan for it was a challenge. It seems that in every era it gets rebuilt. In the 1950s the bridge was built. And in the 70s MBTA moved the Orange Line underground and realigned the roads. At that time, the station was built and it disconnected Washington St.; it stops and starts again. Now our project came in to provide a new, better solution.”

The Casey Arborway project included the demolition of the aforementioned structurally deficient Monsignor William J. Casey Overpass and the MBTA’s Forest Hills Station upper busway canopy, north headhouse, and vent structure, as well as the construction of an at-grade parkway system, expanded transit hub for bus and subway access, new facilities for pedestrians and bicycles, the reconstruction of 12 intersections, construction of a fully accessible north headhouse at the MBTA Forest Hills Orange Line subway station, reconstruction of the MBTA upper busway canopy and construction of the busway extension structure, and replacement of the MBTA Orange Line tunnel emergency ventilation system. Moreover, 4 miles of sidewalks and paths were expanded and widened, with improved pedestrian desire lines and accessibility; 3 miles of new off-street bicycle paths were added, as well as innovative intersection treatments, including a “bike-about,” one of the first bicycle-only, mini-roundabouts constructed in the U.S. and the first in the Northeast.

“The new bicycle infrastructure connecting the Southwest Corridor Park paths to the Arboretum and Franklin Park removed a critical gap in bicycle infrastructure,” Kapust said.

In short, a reinvention of the entire area. Getting there was a matter of long-term planning and coordination and a dynamic design that attempted to give, as Kapust puts it, “everyone what they needed and an improvement over what was there before.”

Aspects of design

The roadway aspect of the project concerned a 1-mile east-west limit, which is the Arborway itself, the former location of the removed bridge, with Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum sitting on one end and Franklin Park on the other, as well as a shorter ½-mile north-south limit.

The project coordinated all signals along three corridors so that traffic movements could have the maximum amount of throughput. Each major intersection was redesigned with all users in mind.

At the intersections at South and Washington Streets, east-to-west traffic now uses median U-turn intersection designs. Left-turning traffic passes straight through the intersection, making a U-turn offset from the cross street and then turning right onto the destination street. Removing left turns increased the volume of traffic the intersection can now handle.

The James Shea Traffic Circle at the entrance to Franklin Park Entrance had been dangerous to navigate for all travel modes. A new signalized intersection was installed and now allows safe bicycle and pedestrian park access and simplifies vehicle movement.

Connecting the Southwest Corridor Park bicycle paths and pedestrians to the Arborway and Washington Street was a particular challenge. Bike speeds needed to be controlled, and consideration for foot traffic, notably students and other children, had to be a top priority. The solution chosen was the “bike-about,” the design for which slows bicycles traveling through the intersection and equalizes all three paths entering the roundabout. Pedestrians use a crosswalk on one of the path approaches, minimizing conflicts. The bike-about also serves as a grand trailhead for the park.

“The Southwest Corridor pass—which continues to the north toward Boston—is one of the most traveled bike paths in the city, along with the Minuteman Path,” said Kapust. “Because of the nature of the path, the number of commuters, and the fact that it changes to an east-west movement, there was a desire to equalize the movement and avoid someone coming to a T and having to deal with bicyclists going 20 mph—and with electric bikes even faster. It’s a commuter route but also a recreational path, and we didn’t want all that meeting at one point. We had tried something like this out in Colorado, and it was quite successful. We wanted to keep it small to keep bike speeds low, but make it easy to maintain—you can navigate it with a maintenance vehicle or a Bobcat to plow snow.”

On the other side of the new Arborway, the roadway alignment passes over the former MBTA north headhouse and vent grate system, which included 12 tunnel roof openings that needed to be closed. The tunnel openings were closed using a variable depth integral concrete slab designed to accommodate the increased loading of a new roadway. Finite element analysis with staged construction loadings was used to design the integral slab and verify that the composite structure did not overstress the existing components of the tunnel structure.

“The tunnel was interesting from a utility perspective as well,” Kapust pointed out, “because it was designed with the expectation that no one was going to change the design features above, so there were only so many points in the tunnel ceiling we could connect to for drainage. So it was a matter of grading the above features to be able to reach those points or chasing back with pipes to the original points underground.”

The original roadways and plazas built on the roof of the rail tunnel were graded and drained to specific points, and the tunnel sections outside the existing roadways were not designed to hold HS20 loading, nor the additional dead loads required to meet the proposed grading requirements. Significant modifications were thus needed to accommodate the new design. As the tunnel contains the terminus of the Orange Line, a commuter rail station, and is pass-through point for the Northeast Corridor, long-term rail closures were not an option. A new drainage system was placed on top of the tunnel using grates cast into the curb and connected to multiple, smaller diameter pipes, which ran to the original outlet points and drainage chases in the tunnel roof. Geofoam blocks were placed under new landscape grading to limit loading on the tunnel. The old vent grate opening and demolished headhouse (12 open holes totaling 2,000 sq ft) also needed to be closed from above. Without the available structural capacity to simply “fill in” the open holes and place a new course of bituminous pavement to meet the grading requirements, a new integral concrete deck was designed to both cover the existing tunnel openings and increase the negative and positive moment capacity of the tunnel roof to accept the increased loading.

The demolition of the bridge and relocation of surface roadway to the south allowed for extension of the Orange Line platform and new fully accessible headhouse on the north side of the Arborway corridor, providing platform access for MBTA customers without having to cross the street. The use of a glass curtain wall system creates the appearance of a greenhouse conservatory. The MBTA Forest Hills Station North Plaza now provides direct paths for patrons, while opening the plaza to other potential uses.

“In the former layout of the area, everyone had to cross the street to get to the station. If you were getting on the Orange Line you had to cross the street,” Kapust said. “Now, if you live on the north side and you want to get to the Orange Line, you do not have to cross the street, because of the headhouse. If you’re a commuter, that’s a game changer. You could see anecdotally that once the headhouse opened, the number of commuters crossing during rush hour was significantly lower than before. And people driving get benefits from that foot traffic reduction, too.”

Utilities

As on every road reconstruction project, utilities presented a challenge for designers and contractors alike. On the Casey Arborway, water lines were the biggie.

“The east-west corridor in this project site carries the two major water authorities in the region: The Boston Water and Sewer Commission and the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority,” Kapust said. “These are huge trunk lines—60-in.-diameter water lines. And they do not have redundancies for these lines. So we wound up installing at least a half-mile of water line.”

Negotiating underground movement in this area was far from easy.

“A lot of this area is utilities,” Kapust recalled, “if you look at a plan for any of the north-south streets like Washington Street, it is utilities from one side to the other, and so it was very difficult to add or relocate because all the underground was taken up already.”

Nonetheless, designers were able to complete utility work with no disruption of service.

Enhanced Public Awareness, Sustainability

The Casey Arborway’s planning study investigated not only the bridge replacement but also at-grade solutions. This included a public involvement process that fully engaged participants with the project team through workshops, meetings, and feedback requirements. A 30-person advisory task force was formed during the planning process representing neighborhood interests, regional advocacy groups, and multiple city and state agencies. More than 40 public meetings and workshops were held during the course of the project in planning and design. Participants were required to do “homework,” such as photographing what they wanted to see as part of the project, developing goals and objectives, and defining desire lines. The regular influence of the public on design is evident in additional roadway crossings for pedestrians, direct connections for side neighborhoods to the Arborway, relocated taxicab stand at the station and bicycle infrastructure, such as a bicycle repair station and bicycle signals.

The project is situated in the Olmsted-designed Emerald Necklace park system, listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is also a transportation hub—34,000 daily vehicles travel the Arborway. The project required carefully balancing the needs of each mode to improve travel while reconnecting park land. Defining this as “a park that has a road through it,” rather than a “road with parks adjacent” resulted in the cohesive streetscape design. This project planted 560 new trees, created 1.9 acres of new open space, and added more than 3 miles of pedestrian paths, 130 accessible ramps, and 4 miles of bicycle paths and lanes. The streetscape was designed with permeable pavers and green-space along sidewalks and bike paths, with runoff helping to water the trees. The park improvements are dramatic. The Arborway once again connects Franklin Park and Forest Hills Cemetery to the east with Arnold Arboretum to the west and Southwest Corridor Park to the north.

Jamaica Plain now finally has the mobility it has always deserved.

About The Author: Budzynski is senior managing editor of Roads & Bridges.