By: Becky Crowe and Mark Doctor

Pedestrian refuge islands are an effective tool of road diets used to reduce the exposure time experienced by a pedestrian in an intersection.

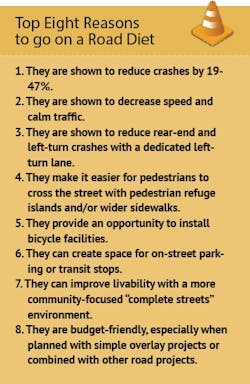

Is there really a low-cost strategy that reduces crashes and improves mobility for the wide variety of highway users? Does that sound too good to be true? Well, a “road diet” is a low-cost countermeasure that has proven to reduce crashes and offer opportunities to “remake” a street into a facility that better suits the needs of all users.

A road diet is a reconfiguration which typically reduces the number of travel lanes to create space for other street elements such as bicycle lanes, a center left-turn lane, medians or curbside parking. Often, road diets do not actually narrow the physical width of a roadway footprint, but instead rearrange how space is used curb to curb.

The Federal Highway Administration’s Road Diet Informational Guide (FHWA-SA-14-028) includes safety, operation and quality-of-life considerations from research and practice, and guides readers through the decision-making process to determine if road diets are a good fit for a given corridor.

A common road-diet configuration reduces four lanes to three. This road diet on Soapstone Drive in Reston, Va., reduced crashes by 67% in the first three years of implementation.

Do all road diets look the same?

There are many options for reconfiguring a roadway, but a road diet usually involves removing or narrowing one or more vehicular travel lanes and utilizing that space for other purposes. A typical road diet takes a four-lane undivided road and converts two lanes in each direction into a single lane in each direction with a two-way left-turn lane. This configuration also may make room for bicycle lanes or on-street parking.

Road diets also may serve to calm traffic. Transportation departments and engineers should consider a road diet if a specific corridor has frequent crashes, high incidents of speeding or passes through sensitive areas, such as school zones or recreation areas.

A road diet also may make it easier for pedestrians to cross the street and create room for cyclists. Decreasing the number of road lanes reduces pedestrian exposure to traffic when crossing the street, and the extra space can be used to add pedestrian refuge islands. For bicyclists, road diets can provide an opportunity to add bicycle lanes that are separate from motor-vehicle lanes, which can be appealing to local bicyclists. A road diet also provides an opportunity to have bus pullouts. Transit users can look forward to safer commuter stops that do not hinder the flow of traffic.

Road diets are generally inexpensive to implement, especially when planned in conjunction with resurfacing projects where the road diet itself would consist primarily of restriping (or repainting) into the new configuration. Additional features, such as building pedestrian refuge islands or modifying the intersections (perhaps into roundabouts), may influence the cost of a road diet.

But do they really work?

In Reston, Va., a 2-mile stretch of Lawyers Road underwent a road diet as part of a scheduled repaving project. The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) implemented this road diet and successfully improved all-around safety and operations for travelers. The road reconfiguration was so successful that it was the recipient of a 2015 National Roadway Safety Award for Infrastructure and Operational Improvements.

The objectives of the Lawyers Road project were to reduce crashes and speeding, and improve safety and connectivity for bicyclists. Prior to the installation, Lawyers Road had two lanes in each direction. Upon completion of the road diet, the corridor now has one travel lane and a bicycle lane in each direction, separated by a two-way left-turn lane.

Randy Dittberner, past regional traffic engineer at VDOT, led the project’s development. In a recent interview with the FHWA Office of Safety, Dittberner stated, “If you build a road diet with a paving project, it can be done at almost no cost. There are huge safety and livability benefits, as well as ‘extras’ like bike accommodations. Why wouldn’t you want to apply a road diet when there are so many benefits?”

A before-and-after analysis of speeds confirmed that operating speeds were reduced after road diet implementation without reducing travel time. In response, VDOT lowered the speed limit on the 2-mile section of Lawyers Road from 45 mph to 40 mph. Five years after the conversion, a safety study revealed a 70% reduction in crashes on Lawyers Road.

In the fall of 2010, VDOT conducted a survey to gauge the community’s thoughts regarding the road diet installed on Lawyers Road. The key findings were as follows:

- 69% of respondents said Lawyers Road seemed safer after the road diet was implemented;

- 47% of respondents bicycled on Lawyers Road more often than before, indicating that the road diet encourages bicycling as a travel mode;

- 69% said auto travel times have not increased, even though 59% said speeds dropped; and

- 74% agreed the road diet project improved Lawyers Road.

Loop-in the public

Public outreach is a critical part of any road diet implementation plan. The term “road diet” can be misinterpreted to imply more congestion by virtue of lane reduction, therefore public outreach is a critical part of countering this misconception. In many cases, road diets can be implemented without restricting the flow of traffic.

In the example of the Lawyers Road project, VDOT’s team led efforts to clearly explain to the public how a road diet could improve their community. Travelers found comfort in knowing that this effort was not an attempt to impose travel restrictions, but rather a roadway safety solution for all road users.

Agencies should focus on promoting the increased safety and livability benefits when conducting outreach with the public. After all, the institution of such projects is ultimately intended for and designed to benefit them.

Context is Paramount

Although road diets can improve safety, and the benefits to pedestrians and bicyclists are readily apparent, they may not be appropriate or feasible in all locations. Transportation agencies should consider numerous feasibility factors and the overall objectives of the corridor in question when deciding whether a road diet is the best solution.

The overall volume of traffic on the roadway is one important consideration. Although road diets have been successfully implemented on some corridors with volumes in excess of 26,000 vehicles per day (vpd), many agencies will limit their consideration of road-diet application to roads with less than 20,000 vpd—the logic being that a lower vpd corridor is less likely to endure possible congestion issues as a result of the road diet intervention. Perhaps more critical than overall traffic volume is the volume and patterns for left-turning traffic. Many four-lane undivided roadways begin to operate in a manner similar to a three-lane roadway as the number of access points and left-turn volumes increase. In this condition, the four-lane undivided roadway may be operating as a de facto three-lane roadway and the operational impacts of reconfiguring to a road diet may have little to no impact on traffic flow.

Other considerations for the feasibility of a road diet may include the number and spacing of intersections and major driveways, the frequency of stopping and slow-moving vehicles through the corridor, the existence of at-grade railroad crossings, and needs for accommodating large truck movements.

A road diet properly applied can be considered a community-building infrastructure investment.

Low-cost results

As funding to improve roadways becomes more and more limited, public agencies search for cost-effective, practical solutions to meet the safety and operational needs of all users. Although road diet projects are typically low cost, agencies also may implement them through other programs, such as pavement overlays or restriping.

Road diets reallocate roadway space within the existing footprint, eliminating the need for purchasing property, lengthy environmental studies, complex design plans, manipulation or expansion of the right-of-way, and expensive construction. Moreover, road diets are one of the least expensive solutions for accommodating additional modes such as bicycles or transit vehicles.

Road diet projects are usually eligible for funding through federal programs such as the Surface Transportation Program (STP) and Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP), as well as other funding mechanisms. For example, the Washington State Department of Transportation has used funding from such sources as pedestrian and bicycle programs and transit grants. The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has used Safe Routes to School grants for road diet installations. SDOT also monitors the city’s road resurfacing projects to see whether streets scheduled for upcoming roadway overlay projects are good candidates for road diets, allowing the agency to use annual paving program funds for some installations.

Discover road diets

Across the nation, more and more states are institutionalizing road diets for standard practice. This comes as no surprise. When planned out and tested, road diets work.

The Federal Highway Administration offers a variety of road diet-related technical assistance including:

- Reviewing a state’s draft road diet policy or guidance documents;

- Development of a road diet presentation aimed at either leadership or the general public;

- Animations demonstrating how road diets improve safety;

- Providing design guidance about unusual road diet configurations;

- Providing examples of other road diets around the country that are similar to the requestor’s road diet; and

- Providing guidance about road diet implementation, including selecting candidate locations, capacity constraints, public outreach response, evaluation metrics, EMS, slow-moving vehicles, cost or funding.

For more information on FHWA road diet workshops, visit: http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/road_diets/resources.

About The Author: Crowe is a transportation specialist with the FHWA. Doctor is a safety and design engineer with the FHWA.