Where the rubber meets the rail

Rail-highway crossings present a special set of safety challenges for transportation professionals.

Due to their vastly different mass and maneuverability, motor vehicles and trains have very different operational characteristics. Quite often, an inattentive driver who makes a mistake at an intersection is saved by the quick evasive actions of other drivers. Grade crossings offer far fewer crash-avoidance possibilities.

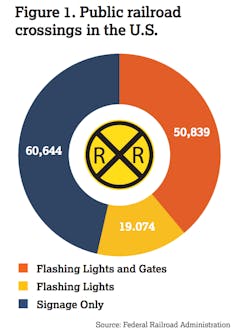

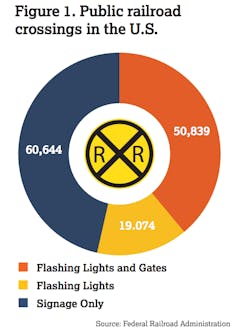

According to an inventory compiled by the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA), in 2017 there were more than 130,000 at-grade railroad crossings on public streets and highways in the U.S. (Figure 1). The FRA also reports that in 2017, a total of 2,108 incidents occurred at railroad crossings, resulting in 273 fatalities and 816 injuries.

The safety issues associated with railhighway crossings need to be considered in the context of the overall roadway safety problem in the U.S. According to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), motor-vehicle crashes are currently the country’s secondlargest cause of unintentional death. More than 37,000 Americans died in motor-vehicle crashes in 2016, and about 3.5 million were injured. In addition to incalculable personal and emotional impacts for victims and their families, the CDC estimates the medical costs and work loss resulting from motor-vehicle deaths totals more than $41 billion each year, with additional costs for non-fatal crashes.

The safe system approach

The U.S. has considerably higher traffic casualty rates than most other high-income countries—even countries where people drive a lot. For example, the World Health Organization’s 2015 Global Status Report on Road Safety estimated that the overall highway death rate per 100,000 people was 10.6 in the United States, 6.0 in Canada, 5.4 in Australia and 2.8 in Sweden. In other words, the per capita motor-vehicle fatality rate in the U.S. is nearly four times the rate of that in the bestperforming country.

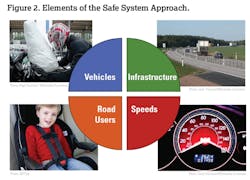

To accelerate the pace of road safety progress, several countries are transitioning from the traditional “Three E’s of Safety” (engineering, education, enforcement) to the Safe System Approach (Figure 2). It focuses on the continuous interaction of vehicles, roads and infrastructure, road users (such as drivers and pedestrians), and traffic speeds. The premise of the Safe System Approach is that if any one of these four elements fails, the other three should be sufficient to prevent a fatality or serious injury from occurring. In other words, the energy released by a crash needs to be kept to a level that a human can survive.

Advances in automotive engineering such as airbags, anti-lock brakes and electronic traction control support the Safe System Approach. There are also many opportunities to improve safety performance—at rail crossings and on the highway system as a whole—through infrastructure investments, road-user behavior changes and speed management.

Current practice

Traditionally, railroad crossing safety efforts have involved three main activities:

- Behavioral interventions, such as the Operation Lifesaver program, which attempt to increase safety awareness with messages such as “Trains Can’t Stop, You Can”;

- Grade crossing signalization projects that upgrade existing crossings by adding train-activated warning lights, gates or both. Currently, the installation cost typically ranges from about $150,000 to $250,000 per site; and

- Grade separation projects that aim at eliminating conflicts between road and rail traffic by building underpasses or overpasses. Due to high construction costs (and impacts on adjoining properties), these projects are typically limited to locations with very high levels of road and rail traffic. For example, a recent engineering study estimated the cost of a fairly typical grade separation project in Anoka, Minn., at $19 million.

Money matters

Currently, federal funding for grade crossing safety upgrades is limited. For example, in federal fiscal year 2017 Congress apportioned more than $41 billion for transportation projects, but just $230 million (about 0.6%) was devoted to the Rail-Highway Crossings Safety Program. The rail safety apportionments for individual states ranged from $1.2 million to $19.5 million, with only three states receiving more than $10 million.

The scarcity of crossing safety funds creates important challenges for transportation agencies. For example, there are nearly 4,300 public railroad crossings in the state of Iowa, including roughly 2,500 that are currently unsignalized. Iowa’s share of the 2017 crossing safety funding was approximately $5.5 million—enough to signalize about 1% of the crossings that currently have only static signs.

In everyday speech, the words “hazard” and “risk” are often used interchangeably. In safety science, these words are assigned distinctly different meanings: A hazard is a potential source of harm, while risk takes into consideration the likelihood and scale of deaths, injuries, and property damage resulting from the hazard.

Federal law requires every state to define a process for selecting rail crossing safety projects. Many agencies currently use selection methods based on a crossing safety model developed by the FRA in the 1980s. The model analyzes only two types of crossing safety projects: flashing lights and flashing lights with gates. It is a hazard-based approach, driven mainly by highway traffic volumes and the daily number of trains.

Some agencies have transitioned to a risk-based project selection approach. This differs from hazard-based methods by incorporating additional factors. For example:

- Crossings that carry passenger rail traffic might be considered higher priorities for safety treatments than freight-only crossings, due to the increased risk of human casualties;

- Crossings that serve a large number of buses have an increased probability of multiple-casualty crashes;

- Crossings that are frequently used by trains or trucks carrying hazardous materials could be considered more risky than those where hazmat is rarely transported; and

- Crossings transporting hazardous cargo that are located in populous areas represent a higher human health and safety risk than crossings with similar traffic in sparsely populated areas.

To some extent, the safety project selection process is similar to developing an investment portfolio: A person with a specific amount of money to invest could buy several shares of a low-priced stock or a few shares of a high-priced stock. Similarly, an agency or railroad could invest in several low-cost crossing safety projects or put all of its funding into a single high-cost project such as a grade separation.

A special low-clearance cars-only mini-tunnel in Tunisia.

Crossing safety around the world

Several advances in crossing safety project selection methods have occurred in recent years. For example, in 1998, East Japan Railway Company became one of the first organizations to adopt a risk-based project selection approach. In 2004, Transport Canada developed a method to pinpoint underperforming crossings by predicting the expected crash rate for each crossing and comparing it to the actual crash rate. And in 2010, the British Rail Safety Standards Board began developing Axiat, a software program that evaluates grade-separation projects using the combined benefits of crash avoidance and traffic delay reductions. Several U.S. agencies, including the Iowa, Minnesota, Kentucky and Texas DOTs, have developed notable project selection practices.

New technologies are expanding the menu of options for addressing crossing safety issues. Some of these techniques are readily adaptable to U.S. conditions, while others are perhaps too radical for American transportation agencies and railroads. A few examples:

In addition to traditional improvement categories, Britain’s Level Crossing Risk Management Toolkit discusses a wide range of safety treatments such as enhanced pavement marking, pedestrian fencing, audible warning devices that adjust to the ambient sound level, antiskid pavement coatings for the crossing approach and red-light cameras to detect crossing violators. The Toolkit also describes some very low-cost treatments, such as large vandal-resistant mirrors to improve visibility at unsignalized crossings where the sight distance is limited by hills, curvature or vegetation.

In some French cities, special low-clearance tunnels suitable only for automobiles are used to reduce the cost of grade-separated crossings on urban streets. Heavy trucks, buses and other tall vehicles are directed to crossings that provide full vertical clearance. This reduces the complexity of constructing grade separations in areas that have extensive underground utilities, underground mass transit systems or similar constraints.

Traditional electromechanical train detection methods often require costly train-control system modifications when a crossing is signalized. To reduce these costs, a train detection system based on acoustic sensors attached to the rails was developed in Norway. Similarly, agencies in some European countries use radar-based sensors for train detection (radar sensors are used worldwide for traffic detection at intersections).

A train detection system based on acoustic sensors attached to the rails was developed in Norway.

Opportunities for the future

Although rail-highway crossing safety program funding levels remain rather low in relation to the scope of the safety problem, new technologies such as radar sensors have the potential to bring down the cost of crossing safety improvements. Moving from the traditional hazard-based project selection approach toward risk-based approaches is one way to help assure that crossing improvement funds are allocated as efficiently as possible. When selection methods are updated, options can be added to increase the range of safety improvement techniques that can be analyzed and to support safety strategies made possible by new technology. In some cases there also are opportunities to leverage additional funding through techniques such as Tax Increment Financing, but this can only be done objectively if the project selection methodology is designed to take leveraging into consideration. Together, these strategies can help move us toward a safe transportation system.

----------

About the author:

Shaw is a researcher at the Institute for Transportation at Iowa State University. Hans is a senior research engineer at the Institute for Transportation at Iowa State University. Souleyrette is the Commonwealth Chair of Transportation Engineering in the College of Engineering at the University of Kentucky. Savolainen is associate professor and safety engineer at the Institute for Transportation at Iowa State University.