Community sees immediate benefits as new Champ Clark Bridge nears completion

By: Lisa Schoolcraft

For a fairly “straightforward” bridge project, the new Champ Clark Bridge in Louisiana, Mo., is a first for project owners and already is delivering enormous community benefits ahead of its completion later this year.

The new bridge will replace the original narrow five-span truss bridge over the Mississippi River, allowing both the Missouri Department of Transportation (MoDOT) and the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) to work together, along with Massman Construction Co. and designer HNTB Corp., on a design-build project.

For HNTB, the $60 million project, which includes removal of the old bridge, also is a nod to its history.

“Our predecessor company designed the original bridge. To come back almost 100 years later and design its replacement is kind of cool,” said Hans Hutton, P.E., project manager and HNTB’s chief engineer in its Kansas City bridge department. The new bridge is being built 50 ft downstream of the original bridge, which was completed in 1928 and named for James Beauchamp Clark, a former Missouri Speaker of the House. Upon completion of the new bridge, which will retain the Champ Clark name, the old one will be dismantled.

The old bridge, which links Louisiana to Pittsfield, Ill., is just 20 ft wide, with very narrow 10-ft traffic lanes each way and no shoulders. Semitrucks passing each other have been known to lose side mirrors. Wide-load vehicles needing to cross the bridge bring traffic to a halt to ensure safe passage.

The new bridge will offer 12-ft travel lanes and 10-ft shoulders in each direction, more than doubling the roadway width, Hutton said. “This is a rural community with farm equipment and truck traffic traversing the bridge. The current bridge has limited that type of traffic.”

The Champ Clark Bridge sees about 4,000 vehicles per day. “When combines go across, the police shut down the bridge,” said Keith Killen, P.E., MoDOT project director. “This also happens frequently with large loads. The new bridge will be an amazing improvement for the community.” Moreover, the project, which could have been delivered in the traditional design-bid-build method, found unique advantages to going design-build instead. “MoDOT has had the opportunity to use design-build on some of our larger projects,” Killen continued. “We performed a project determination to show us that design-build might be the best way to go forward. Also, the guaranteed budget is a benefit with design-build.”

This last point—working within budget—was critical for project stakeholders.

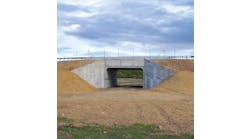

The original Champ Clark Bridge is only 20 ft wide, resulting in frequent temporary traffic restrictions due to truck and farm equipment traffic, not to mention numerous safety issues related to wide-size vehicles requiring more than the 10-ft shoulderless driving lane. The new bridge (pier placement is shown above) will have 12-ft driving lanes and 10-ft shoulders.

“We were given a fixed budget, and MoDOT wanted to know what we could provide within that budget,” said T.J. Colombatto, P.E., project manager for Kansas City-based Massman. “This job is pretty straightforward when it comes to bridges. The first challenge was, how can we enhance this project? What bells and whistles can we give them? We included some little things that would enhance the project like adding roadway lighting to the intersection at the west end of the project. We proposed to give them a polyester polymer overlay on the deck of the bridge. That was a big selling point. And we added 10-ft shoulders to each side of the bridge. We carried the shoulders not only on the bridge but over on the Illinois roadway as well.”

One innovation to the project was using precast deck panels, Colombatto said. HNTB had used precast deck panels before on other projects; the benefit to the Champ Clark Bridge project is to keep it on schedule, he added.

A total of 181 precast deck panels will be used in the construction of the new bridge. Each deck panel will be 46 ft wide extending the full width of the bridge.

Using design-build on the new Champ Clark Bridge had other advantages, too.

“This also is an opportunity for IDOT to see behind the curtain, so to speak,” said Brandi Baldwin, P.E., deputy project manager for MoDOT. “They had not had an opportunity to use a design-build process before. It’s the first design-build project for our district, too, not just for Illinois. It gave us a great opportunity to flesh out what the risks are.”

It also allowed for some innovation on the project, such as the polyester polymer overlay, Baldwin said: “That may be an old shoe for some, but some of the innovation we’ve seen on the project is that overlay. HNTB and Massman brought that to us, the overlay, and we didn’t get that from any other team.”

Another reason to use design-build for the Champ Clark Bridge replacement was the ability to compress the schedule.

“The bridge is 91 years old, so its condition also drives us to want to complete this [new] bridge as quickly as possible,” Baldwin said. “This is a joint-funded project with MoDOT and IDOT, but MoDOT is the lead for the states. We certainly do coordinate with IDOT to make sure we are meeting their needs as well.”

To meet a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers stricture on "no rise" in the water level of the river, Massman used large, 11-ft-diam. drill shafts in the piers, which enabled a reduction in the number of shafts per pier—as well as significant cost savings.

Community benefits

Massman, HNTB and MoDOT officials held monthly community meetings to keep residents abreast of the project’s progress. And while the new bridge is not as yet complete, the community almost immediately saw some improvements.

HNTB wrapped up design a little more than a year ago, and hard construction began in late 2017. “We broke it into three phases,” Hutton said. “The first phase involved some work on the Missouri side of the river, which included resurfacing an intersection to the west of the bridge. There’s a lot of truck traffic that drives through that intersection, and to help them maneuver better, we pulled back some of the curbs and resurfaced the roads. Immediately after the start of construction, [residents] saw something positive. They got a refresh of their driving surface.”

Another community benefit has been to the schools, MoDOT’s Killen pointed out.

“One of the things that we have tried to do with the project is, because we are in a small town, we wanted to take the opportunity to leverage this project into having an impact to local schools,” Killen said. “We have done STEM [science, technology, engineering and math] activities to reach out to local schools to incorporate our project and talk about the benefits and career opportunities in engineering and construction.”

All of the partners have been involved.

“We went to one of our STEM outreaches [recently], and project engineers from Massman taught classes on buoyancy and stability,” MoDOT’s Baldwin said. “We had an awesome hands-on demonstration.”

Project partners also planned to participate in a career fair for nearly 100 area students, she added.

There have been project site tours and even a summer camp for high school students as part of the community outreach, Killen said. “We also did a design challenge where students had to design an interpretive panel that will be part of a permanent display in a park near the new bridge.”

Project stakeholders staged numerous community events related to the project, including STEM activities in local schools and a career fair.

Project challenges

The Champ Clark Bridge replacement project has not been without its challenges, particularly on the permitting required for a new bridge.

“Environmental permitting was a tremendous challenge, and a lot of that took place before we awarded the project to HNTB and Massman,” Killen said. The project required various permits from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Coast Guard, as well as both the Missouri Department of Natural Resources and the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. “Getting those permits before we had a final design was a challenge, trying to get permits for a conceptual bridge. But we wouldn’t get our final design until we had selected our design team.”

Another challenge was the “no-rise condition” during construction, “meaning we can’t raise the water level during construction,” Baldwin said. “This can be difficult to achieve with our need to leave the existing structure in place for the duration of the project.”

There were a number of stakeholders concerned about the no-rise condition, Hutton said, including the Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Coast Guard, levee districts and various landowners in the area. “There has been flooding in that area, so that is a concern with the levees.”

To meet that no-rise condition challenge, Massman used large 11-ft-diam. drill shafts in the piers. “That allowed us to reduce the number of shafts per pier which saves time and money,” Colombatto said. “We had to prove that our bridge design would not cause a rise in the river during a flood event. We also had to prove that our temporary conditions didn’t cause a rise as well. We reduced the number of piers, which helped us achieve the no-rise conditions.”

For Colombatto, one of the points of pride in the Champ Clark Bridge project is the fact that it is a Mississippi River bridge.

“This has been a pretty smooth project,” he said. “We were awarded this project in July 2017, and in just two years we’re going to open the bridge. One could say that our greatest innovation was to develop a simple solution to a complex problem.”

About The Author: Schoolcraft is a freelance writer based in Atlanta, Ga.